The term “whistle stop” was once a pejorative, like the modern term “flyover country.” When Harry S. Truman conducted his whistle-stop campaign for the 1948 election, he popularized the term. Truman, himself being from a “whistle-stop” town (even today its population barely surpasses 4,000), made it clear that in politics, the small towns count. Today, the term is less popular than it is nostalgic, and Edward Segal, in his new book “Whistle-Stop Politics: Campaign Trains and the Reporters Who Covered Them,” has captured the growth, popularity, and nostalgia of campaigning by railroad.

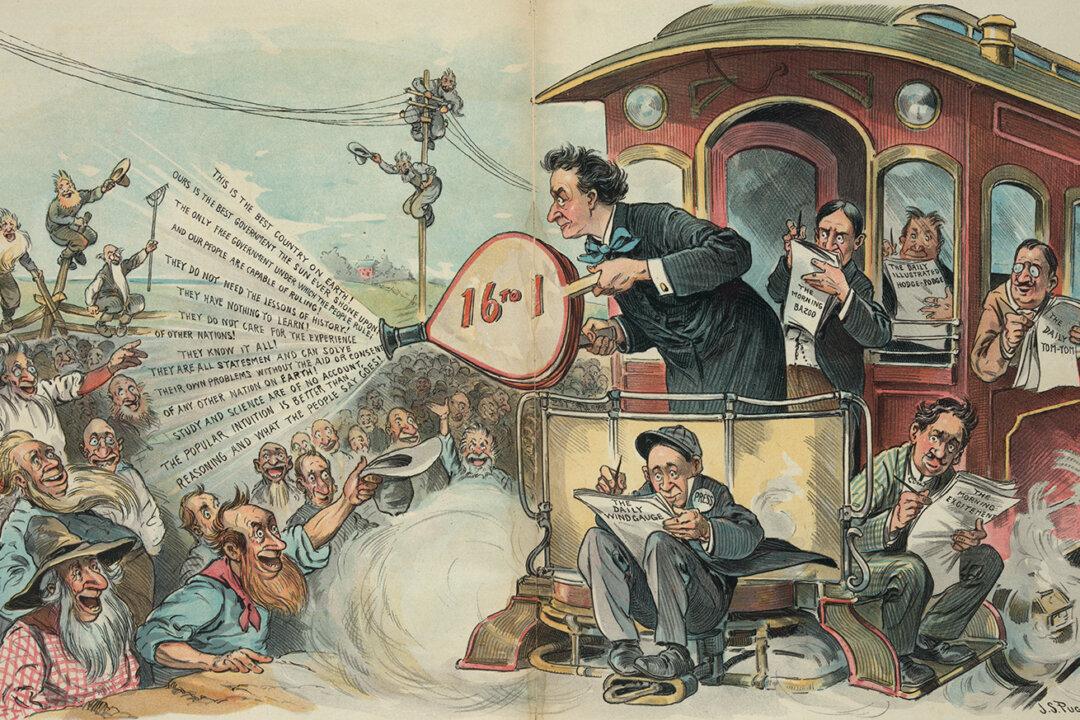

The author dives deep into the details of general political campaigning―the scheduling, the speeches, the news coverage―but by locomotive. When thinking about whistle-stop campaigning, images of candidates yelling from the back of trains surrounded by onlookers and supporters come to mind. Mr. Segal informs the reader that there are so many other images to picture.