Time to break free of the winter doldrums.

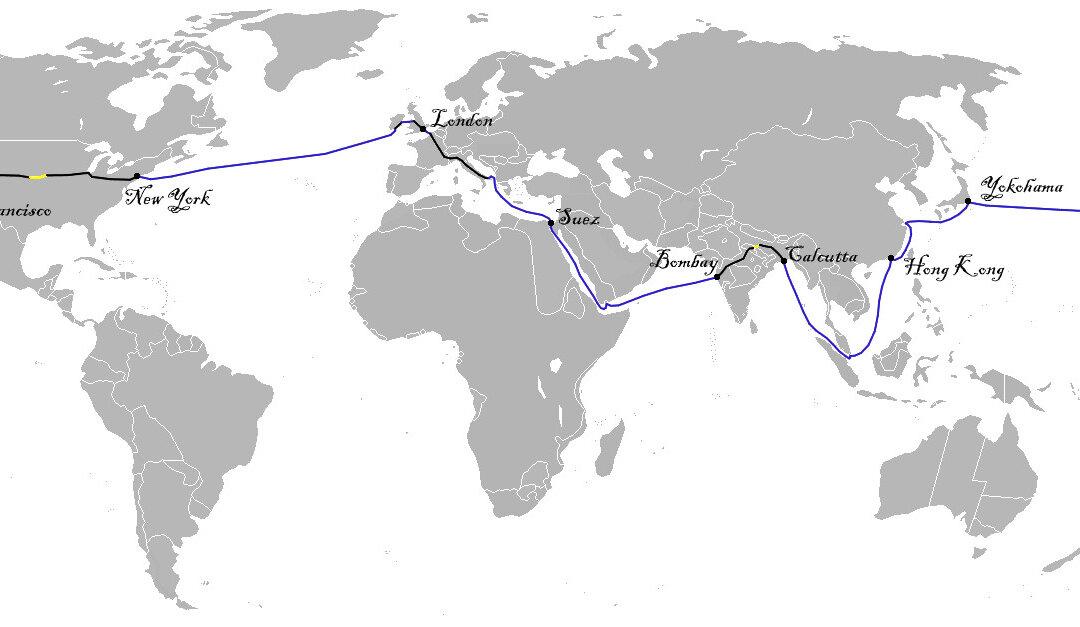

Let’s put aside today’s headlines and instead travel the world. We’ll spend a few days in rural India, pay a quick visit to Singapore, cross the plains and mountains of the American West by rail and on sleds driven by sails, and beat our way across the Atlantic on a steam-driven ship. Along the way we’ll rescue a damsel in distress and face bandits, storms, and other dangers, all the while pursued by an intrepid detective for a crime we didn’t commit and surviving by means of our wits and grit to win a wager.