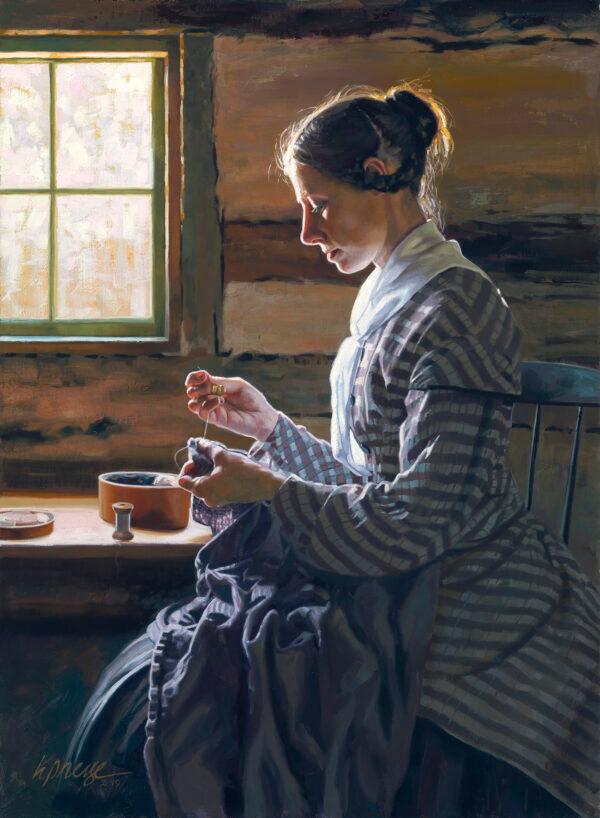

Artist Heide Presse paints mid-19th-century American life as authentically as she can. Farmers, homesteaders, and pioneers are a few of the folk who are captured on canvas, taken from firsthand historical accounts. In her paintings, women read Bibles, sew quilts, or tend children; and men work the land, herd cattle, and drive wagons.

Keturah Belknap in "Not an Idle Minute," 2019, by Heide Presse. Oil on linen panel; 30 inches by 22 inches. (Courtesy of Heide Presse)