CROKER BAY, Nunavut—Two miles across at the snout, the glacier girding Croker Bay forms a towering blue-and-white wall of snow and ice. Cracking and calving, this massive natural wonder—which runs back to an ice cap almost five times the size of Luxembourg—seems to vie for our attention, thundering as it casts off frozen chunks of itself, warding us away from Devon, the world’s largest uninhabited island. But, bundled up and creeping slowly along its intimidating face, my eyes, and ears, are fixed elsewhere, scanning icebergs out on the bay and listening carefully for the next time my guide’s radio will crackle to life, bringing news of their location.

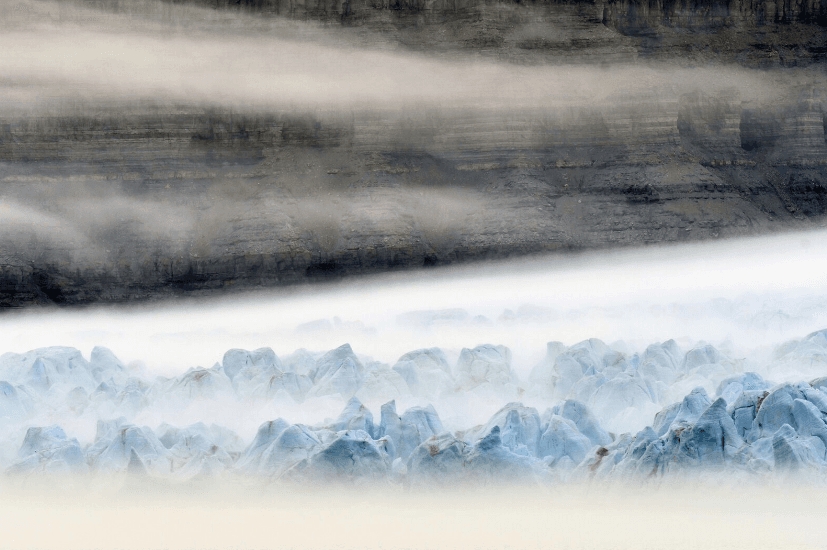

Mist over Croker Bay. Andre Gallant