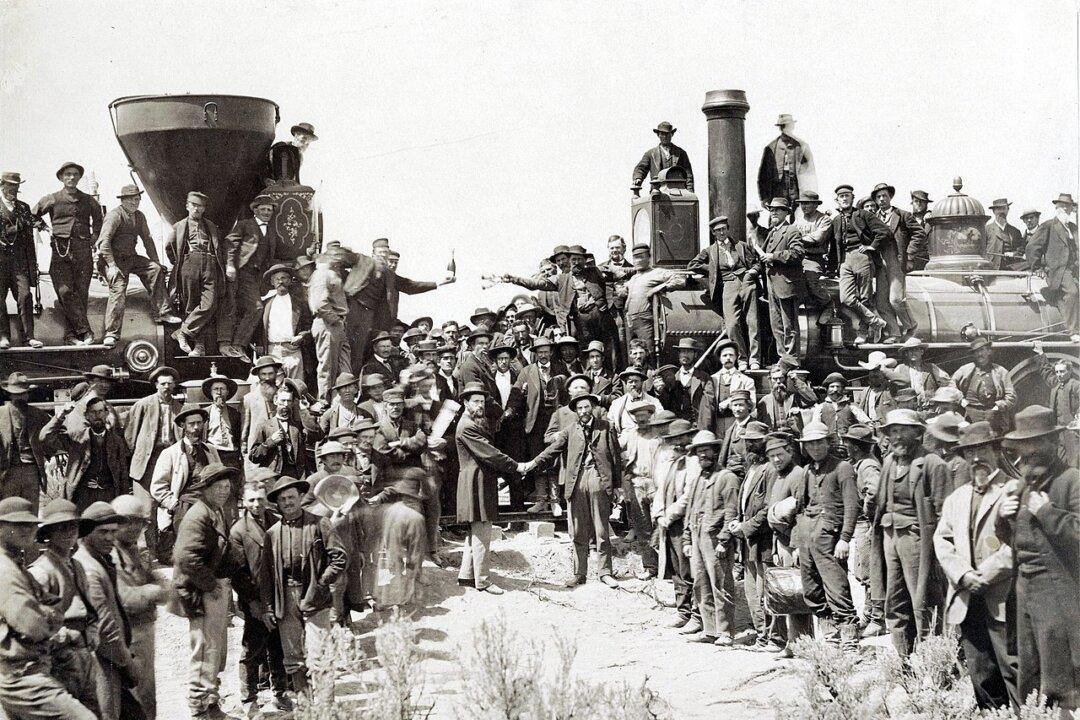

Andrew J. Russell (1829–1902) grew up in the northeast pursuing the life of an artist. As he progressed artistically, he received numerous commissions from political and railroad figures to paint portraits, along with landscapes. He slowly moved into photography by using photos as references for his paintings instead of creating sketches. His move toward photography would not only alter his career, but would alter our view of American history.

Portrait of photographer Andrew J. Russell, 1902, by an unknown photographer, National Park Service. Public Domain