Recently, a New York couple, readers of The Epoch Times, sent me a 1914 edition of “Essentials of English: First Book.” As stated in the book’s preface, the authors, Henry Carr Pearson and Mary Frederika Kirchwey, both associated with Horace Mann School of Columbia University, intended their textbook for “use in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades of the elementary school.”

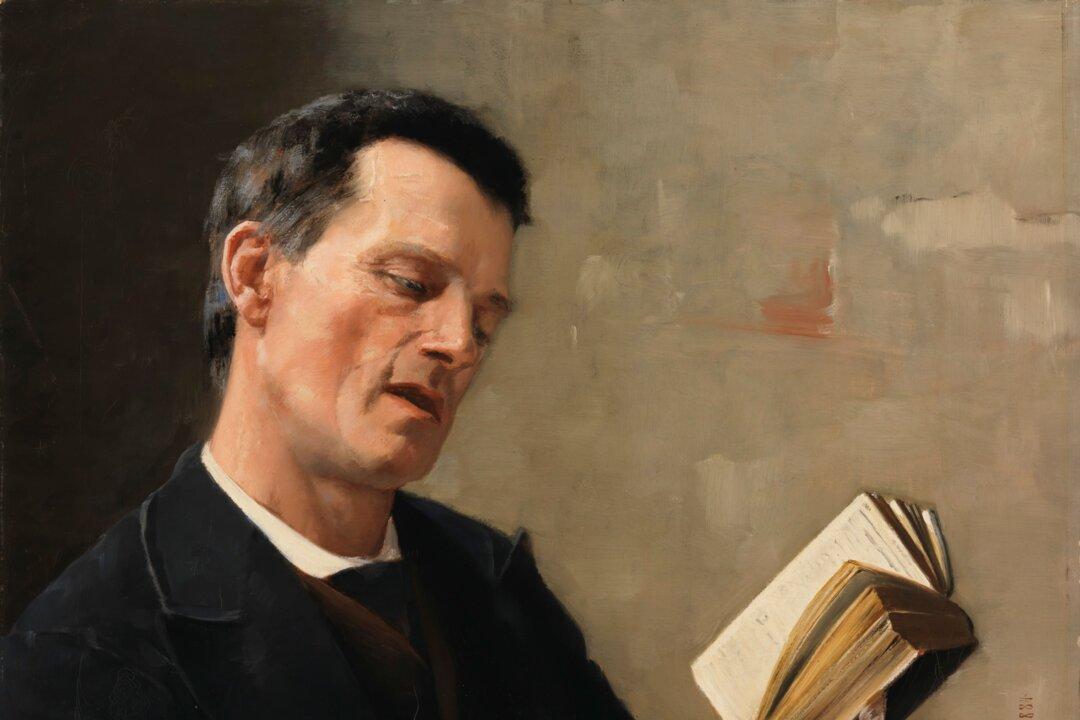

“Essentials” is unremarkable in its physical appearance. It features a few paintings and photographs, and some drawings, but nothing comparable to the illustrations in our modern readers and grammars. Approximately 5 by 7 inches, its exterior is small, drab, and worn, so much so that it’s impossible to tell whether the original cover was green or blue.