The vast prairie stretched in front of the Lewis and Clark expedition, teeming with life and promising new discoveries. In present-day Nebraska, they spotted and described little furry animals we now call prairie dogs. Lewis was amazed by their burrow networks and sheer numbers. One day, Lewis observed a jackrabbit bounding across the plains. “It … is extremely fleet and never borrows or takes shelter in the ground when pursued. They appear to run with more ease and to bound with greater agility than any animal I ever saw,” he wrote.

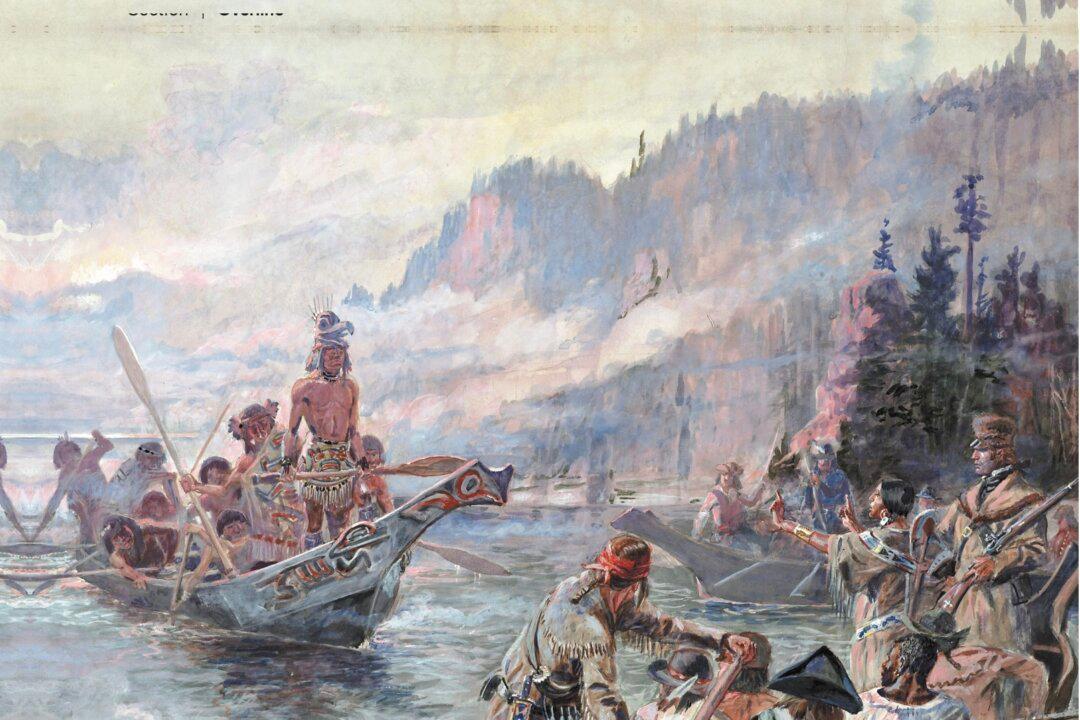

The sheer number of animals that lived on the plains further amazed Lewis and his men. “Vast herds of buffalo, deer, elk and antelopes were seen feeding in every direction as far as the eyes of the observer could reach,” Lewis reported. The plant and animal life of the plains provided amply for the expedition’s table, and some of the Native American tribes they met proved hospitable. However, the ensuing years would test the courage of Lewis, Clark, and their men.