Thinking about the theme of building on the classics, I’ve concluded that nothing could be more appropriate than to ask and answer this question: Why realism?

There are finally today many organizations that believe in the value and importance of realism, both classical and contemporary; but why realism? Why, after a century of denigration, repression, and near annihilation, when the accepted beliefs taught in nearly every high school, college, and university for the last hundred years have been that realism is unoriginal?

After all, all realists do is just copy from nature. Realism, they say, is unsophisticated.

Most people can tell what is going on in realistic painting or sculpture. It’s so easy to understand. It’s uncreative; only creating forms and ideas not found in nature show real originality. So the question of the day for society—and for realist artists, the question for the month, year, and really for the rest of their lives—is: Why realism?

My answer is direct, simple, and should be self-evident: The visual fine arts of drawing, painting, and sculpture are best understood first, last, and always as a language, a visual language.

It was developed and preserved first and foremost as a means of communication very much like spoken and written languages. And like language, it is successful if communication takes place, and it is unsuccessful if it does not. This answer simultaneously defines the term “fine art.” So fine art is a way that human beings can communicate.

And how can one truly communicate, except by a language that is understood by those who are listening? And if communication is the goal, then our language must have a vocabulary and a grammar that is shared by the teller and listener alike.

If you think about it, the earliest forms of written languages used simple drawings of real objects to represent those objects. That makes the origins of written language overlap in a nearly identical way to the origins of fine art.

Without a common language, there is no communication and no understanding, and that holds true as well for fine art. It also must communicate in a similar way to spoken and written languages, which have the uniquely human purpose of describing the world in which we live, and how we feel about every aspect of life and living.

As a language, it is like all of the hundreds of the spoken and written languages that are capable of expressing the enormous, limitless scope of human thoughts, ideas, beliefs, values, and especially our feelings, passions, dreams, and fantasies—all the varied and infinite stories of humanity.

The vocabulary of fine art is the realistic images that we see everywhere throughout our lives, and the grammar is the rules and skills needed to successfully and believably render the images.

These are some of the rules of grammar that hold together the real objects or vocabulary of the visual language of fine art: finding contours; modeling; manipulating paint to create shadows and highlights with the use of glazing and scumbling, which enhance the forms through layers of pigment; use of selective focus; perspective; foreshortening; compositional balance; balancing warm and cool color; lost and found shapes and lines.

Please consider this additional self-evident truth: Even things that are not real such as our dreams and fantasies as well as all stories of fiction—which are not real—are expressed in our conscious and subconscious minds by using real images.

Consider that only real images are used in our fantasies and dreams, none of which look like modern art. Therefore, abstract painting does not reflect the subconscious mind. Dreams and fantasies do that, and artwork can also do that but only by using real images and assembling them in ways that feel like fantasies or dreams.

So, there we have it—fine art is a visual language that is capable of expressing the endless range of thoughts and ideas that can also be expressed in great literature and poetry.

However, unlike the hundreds of spoken and written languages, the vocabulary of traditional realism in fine art has something that makes it unique, in one important way—the language of traditional realism cuts across all those other languages and can be understood by all people everywhere on earth regardless of what language it is they speak or write.

Thus, realism is a universal language that enables communication with all people and to people of all times—past, present, and future.

This is Part 1 of an 11-part series presenting the speech given by Frederick Ross at the February 7, 2014, Artists Keynote Address to the Connecticut Society of Portrait Artists. Frederick Ross is chairman and founder of the Art Renewal Center (www.artrenewal.org).

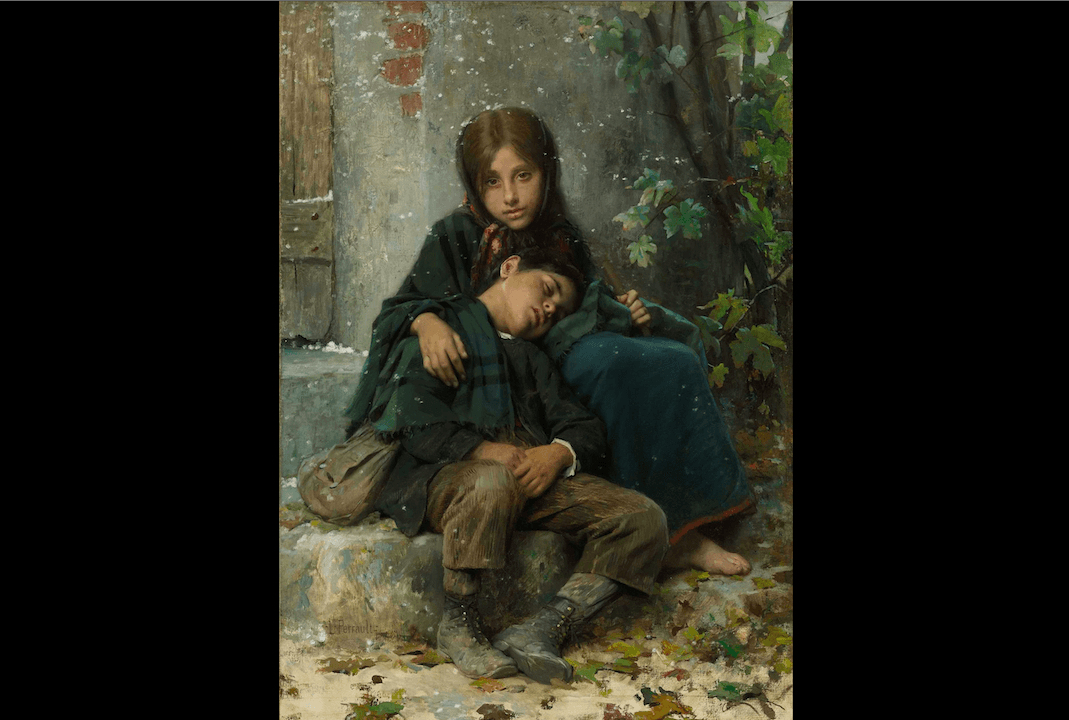

“Out in the Cold,” by Léon Bazile Perrault (1832–1908). Courtesy of Art Renewal Center

|Updated: