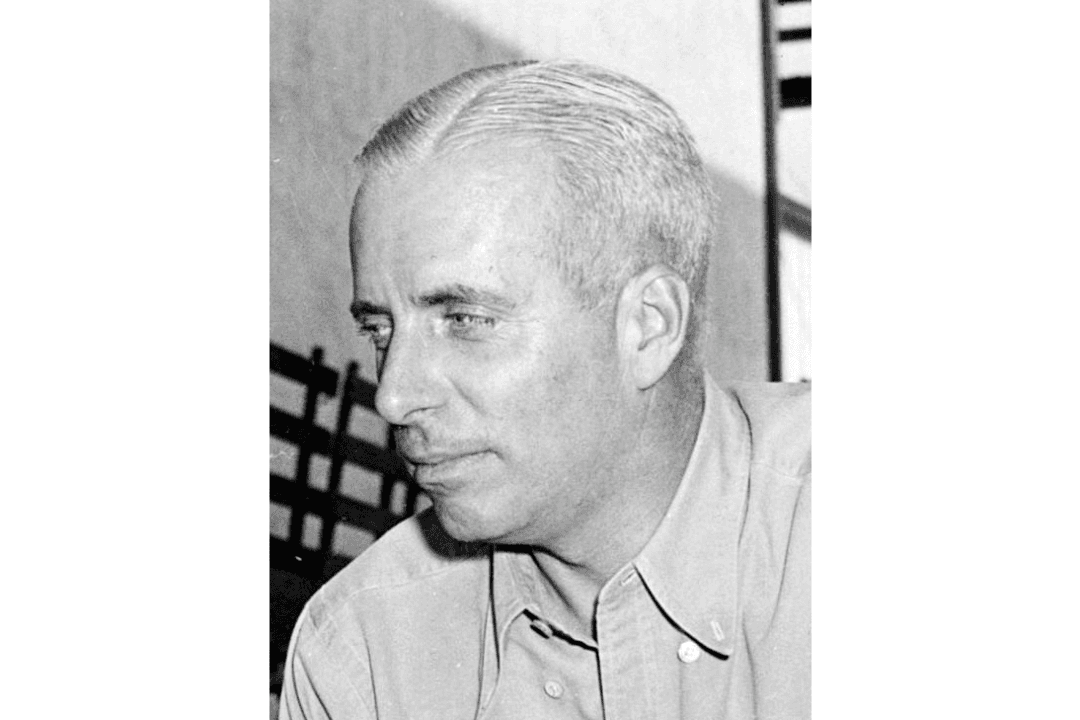

On Sept. 16, 1890, the inventor Louis LePrince boarded a train for Paris. He had spent the weekend in Dijon with his brother Albert, arguing over the terms of their mother’s will. Louis claimed Albert owed him at least £1,000. Albert refused to pay.

Louis was happy to leave this squabble behind. He planned to travel to London, then to New York to rejoin his family and astound the world with the brainchild he’d struggled for years to perfect: motion pictures! But when the train arrived in Paris, Louis didn’t get off. He never made it to London or to New York. In fact, he was never seen again.