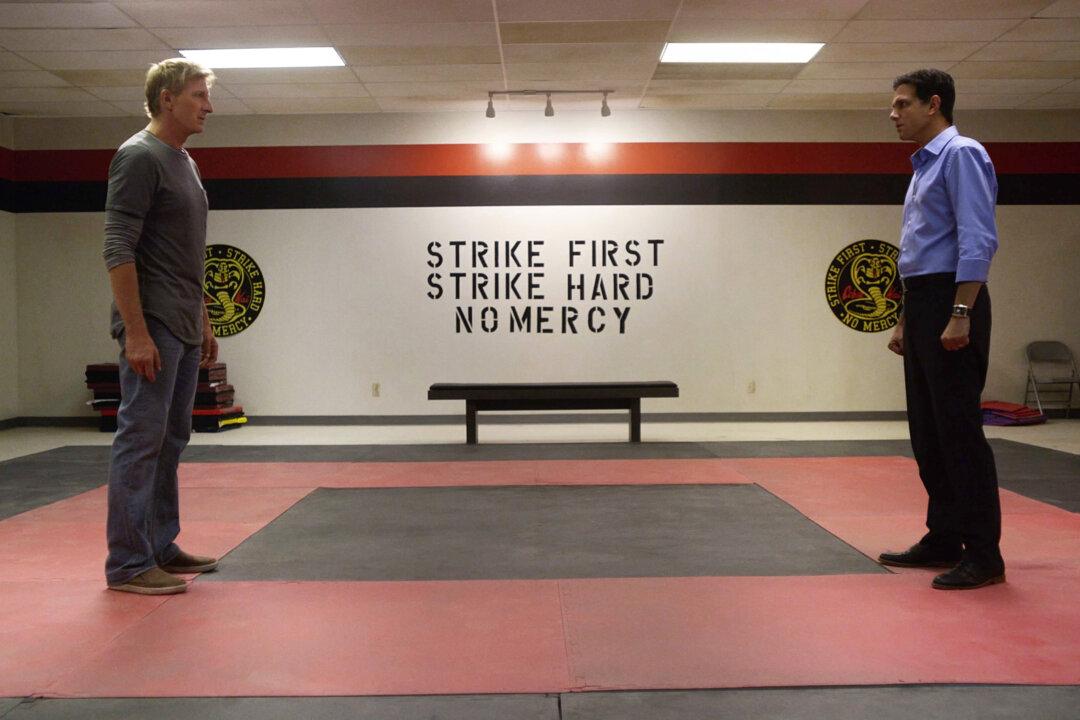

“Cobra Kai” is back. Season 4 began on Dec. 31, 2021, and my family is watching what is perhaps the most surprising hit in a decade—and our personal favorite.

The “Karate Kid” spinoff had “flop” written all over it. After several sequels and reboots, the franchise felt spent. Moreover, it was launched as part of YouTube’s ill-fated plan to compete with Amazon and Netflix in original content production.