For those who survived, their livelihoods are at stake: the pandemic has also shuttered businesses and plunged the country’s economy into its first contraction in decades. Economic losses due to the virus was likely 1.3 trillion yuan ($183.7 billion) for the period from January to February alone, according to estimates by Zhu Min, former deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund.

The devastation has propelled a growing number of Chinese citizens to launch legal challenges against the ruling regime.

Holding the Regime Liable

On March 6, around two dozen lawyers and rights advocates from nine Chinese provinces joined forces with Chinese dissidents in the United States to offer consultancy for victims who are seeking compensation from the Chinese regime.“The responsibility is on the government. It caused a massive outbreak, deaths, and aftermaths, but now commoners are bearing the losses,” Li Fang, a member of the consultancy group, told The Epoch Times.

The group has received at least seven inquiries so far. Two Chinese citizens said their family had lung infections but were unable to get treatment, as hospitals were also overloaded. Both family members died as unconfirmed cases less than two hours after they were eventually hospitalized.

Another claimant, who recovered from the virus, has yet to receive the diagnostic report and is thus unable to file insurance claims.

Yi An (alias), a Wuhan resident who lost his parents to the virus, accused the government of “murder.” Poring over internet posts, Yi said he read about countless tragedies mirroring his. “There has been no apology ... not even a word of condolence from [the government],” he said in an interview. He is currently contemplating legal action. “It’s not for the money. I want to seek an explanation,” he said.

“Someone has to be held responsible,” said Tan Jun, a Chinese civil servant who has filed a lawsuit at the Yichang Xining People’s Court against the provincial government of Hubei, the region where the outbreak emerged.

For the lives lost and upended, the Hubei government must issue a public apology on the front page of the local state-run newspaper, Hubei Daily, Tan wrote in his court filing shared with The Epoch Times.

Pressure

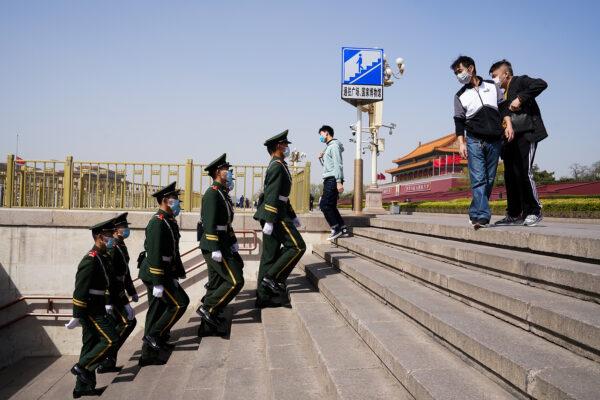

The Chinese regime acted swiftly to clamp down on such acts of defiance.In just over a week after the lawyers’ group was formed, China’s justice ministry issued an informal order banning lawyers from “creating trouble” by getting involved in lawsuits seeking compensation, signing on joint statements, contacting rights lawyers, or accepting interviews from overseas media. It was seemingly a direct response to the group’s efforts, Li said.

At least one person withdrew their legal claim after his workplace discovered his plans. He was criticized for making a “political mistake.”

Yang Zhanqing, a human rights advocate in the group, said local police recently summoned his family in China twice to ask about his activities. They were required to sign a non-disclosure form promising not to speak about their discussions at the police station.

He said that officials will likely do all they can—from offering small favors to making threats—to discourage such legal action, which motivates the group more to fight for people’s rights. “Once it’s filed, it will be a landmark case—whether the court puts it on hold or processes it,” Yang said.

He has drafted a 14-page sample complaint and posted it online with four-step instructions for people to reference.

“Many people have received threats from local governments during our communications [with them] … so I thought it might be better if they don’t need to make contact with us,” he said. “A victim should feel entitled to defend their rights. They [authorities] may claim it’s anti-nation and anti-government, but [people’s rights] are guaranteed by law.”

Around 6 p.m. April 13 evening—within hours after Tan delivered the lawsuit—Yichang city police summoned Tan and his supervisor. They demanded him to stop publishing any materials online, lest these be taken advantage of by foreign media, Tan recalled. The supervisor also tried to dissuade Tan, expressing fears of being fined.

Despite the pressure, Tan vowed to carry on. “The evidence I collected are all government documents. I didn’t make anything up,” he said, adding that he has made sure to keep a copy of each document he filed.

Tan knows the risks of offending the regime; in 2008, he was detained for 10 days after writing a social media post that authorities claimed “defamed national leaders.”

Noting the opaque Chinese legal system that favors Party interests, Tan acknowledged that his chances of winning the lawsuit were slim. He said he is taking it “lightly.”

“They have deployed the national mechanism and exhausted all resources against citizens,” he said. “Winning the lawsuit or not is no longer important for me … it’s better if I can win, but I have nothing to regret.”