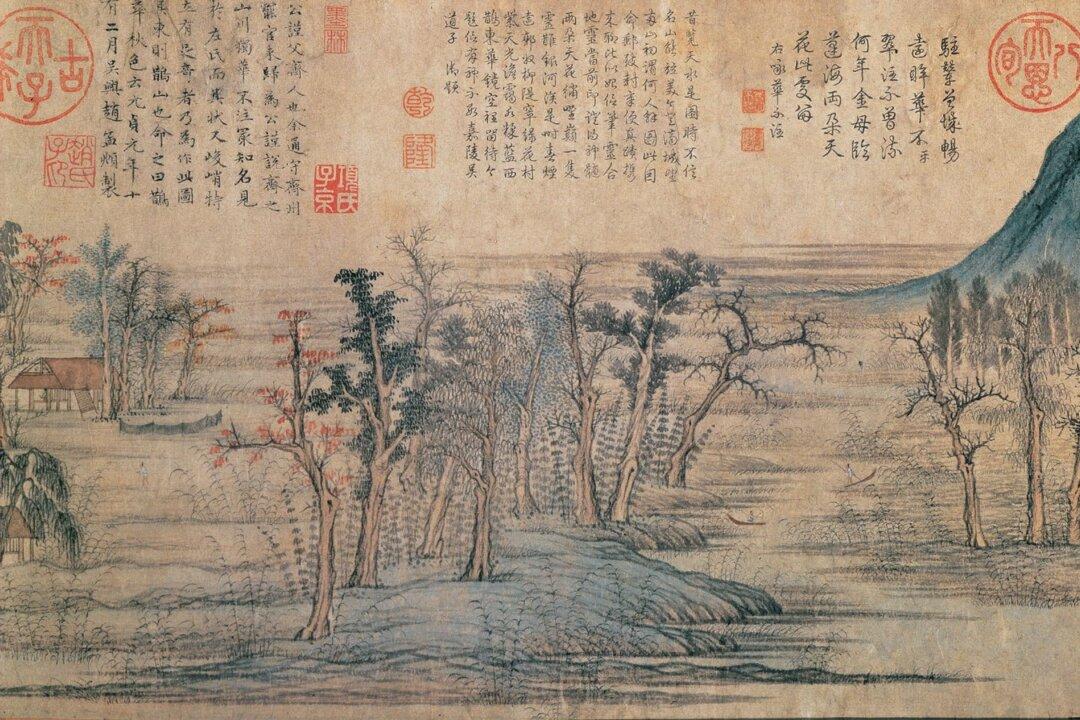

Scandals allure and entice us. While scandalous events are feverishly debated today, the ancient Chinese used such incidents as subjects of art, often to teach moral lessons. These incidents became timeless through art and thereby offered insights into ancient Chinese thought and values that remain relevant to modern-day society.

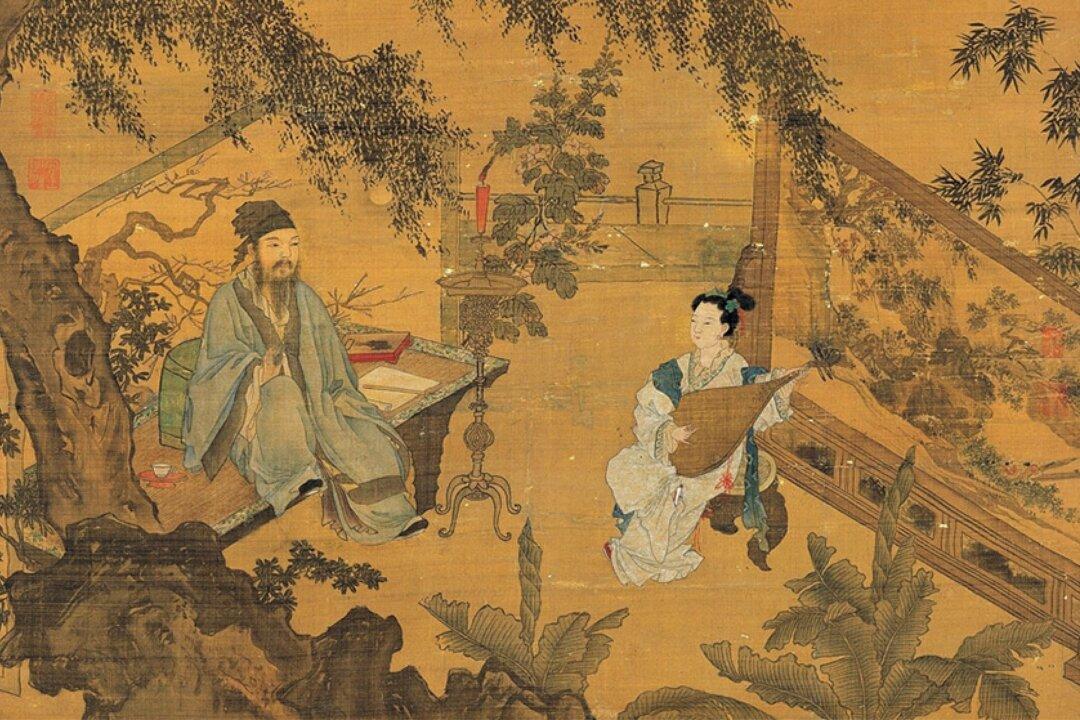

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), artists often depicted women as a common motif. Among these artists, Tang Yin (1470–1524) and Qiu Ying (1494–1552), who were two of the Four Great Ming Masters, featured court ladies and courtesans in their works and drew inspiration from past scandals for their themes.