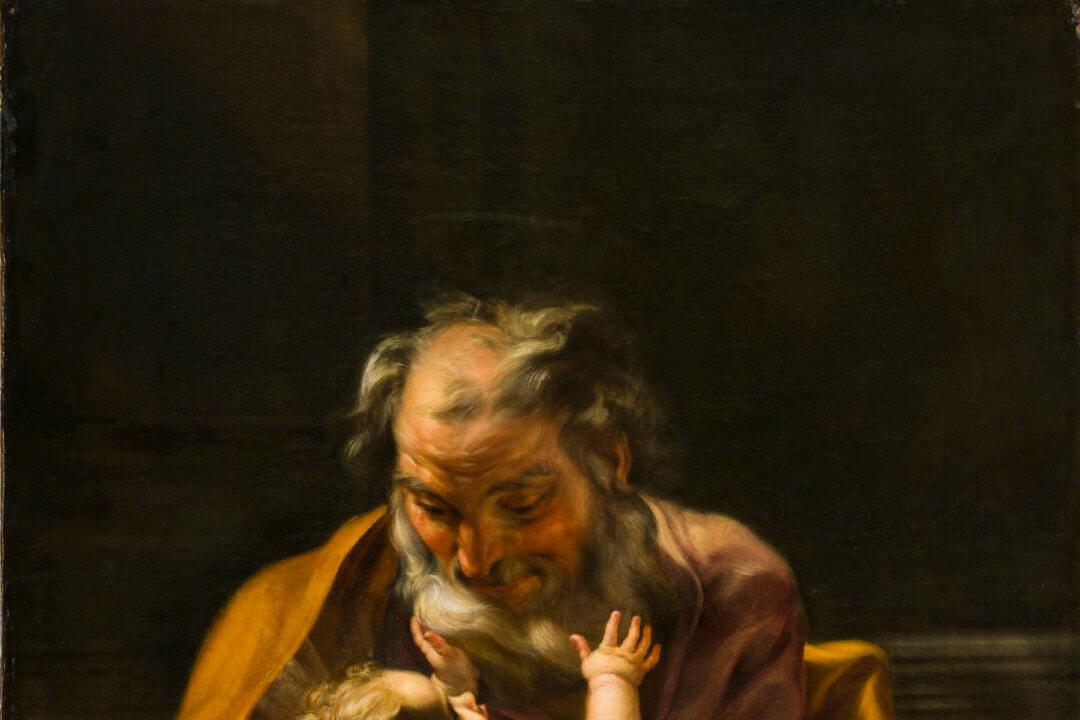

“[T]rue painting is such as not only surprises, but as it were, calls to us; and has so powerful an effect, that we cannot help coming near it, as if it had something to tell us,” wrote French art critic Roger de Piles in his “Principles of Painting” (1708).

Traditional art speaks to our souls—with subjects that gently guide or chastise us—while always offering us ways to become better versions of ourselves.