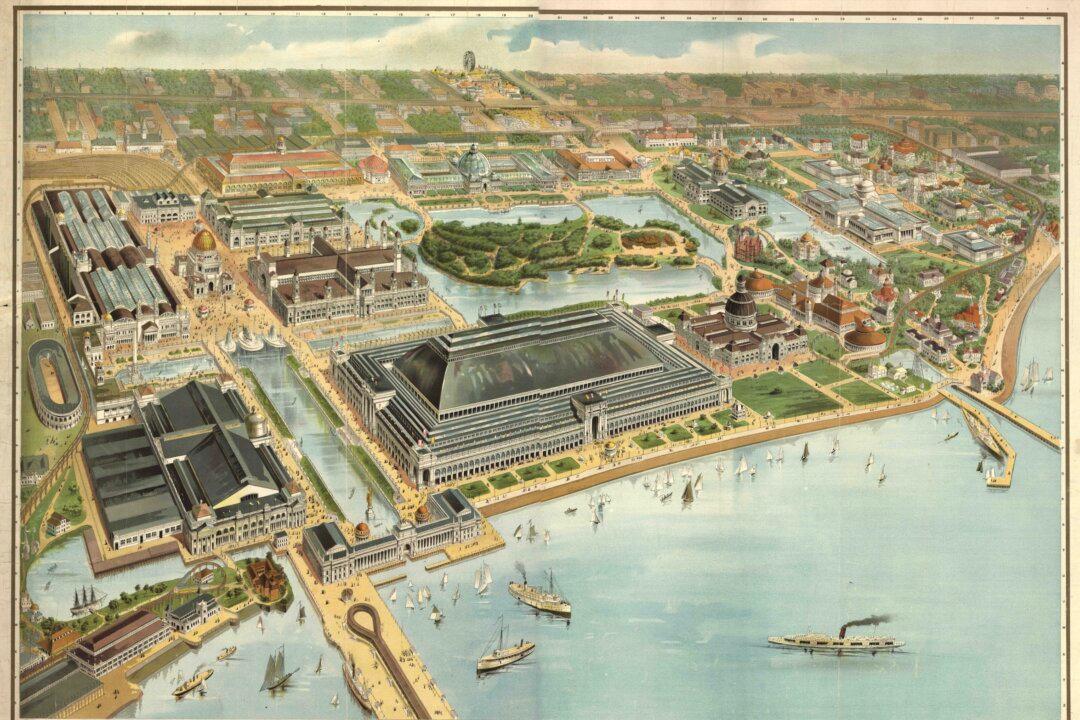

The bustling streets of a prosperous town in colonial America featured a variety of homes, businesses, and shops. Many of these shops were run by craftsmen who performed every service from blowing glass to making furniture.

In this colonial world, American craftsmen relied on an apprenticeship system. Boys served a master for around four or five years, during which they learned the trade. If all went well, at the end of their indenture the apprentices became journeymen and left to earn a living and save up enough to open their own shops as masters.