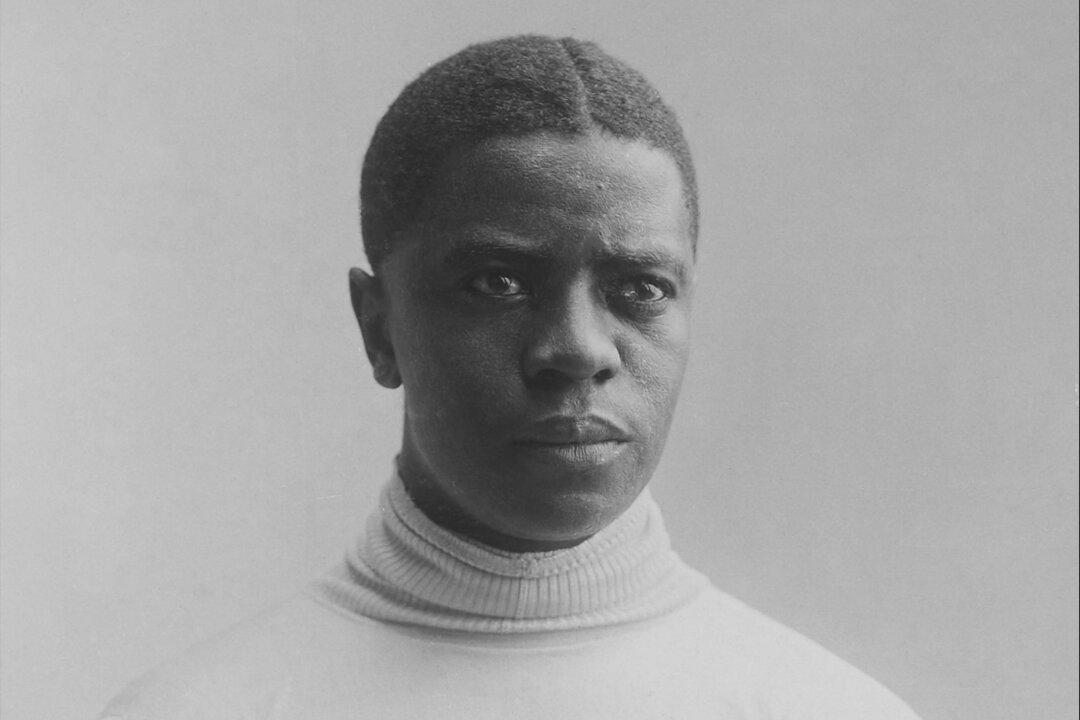

On November 26, 1878, two days before Thanksgiving, Gilbert and Saphronia Taylor welcomed their fourth child, Marshall, into the world. Gilbert, a Union veteran of the Civil War, had moved his family to Indianapolis only a few years after the war ended and his home state of Kentucky began issuing new restrictions on blacks. Indianapolis not only held better opportunities for the young family, but it would open a door for their new son that none would have thought possible.

When Gilbert accepted a job as a coachman for the Southards, a prominent family in Indianapolis, Marshall soon struck up a friendship with the family’s young son, Daniel. The friendship became so close that the family requested for Marshall to stay with them for long periods of time. Though Gilbert and Saphronia were hesitant, they allowed it as long as Marshall adhered to his Baptist upbringing.