Though created nearly six centuries ago, the justly famed double portrait by the Flemish master Jan van Eyck in the National Gallery, London, still holds viewers in thrall. Yet art historians have been unable to determine with certainty who is depicted or what the circumstances and intent of its creation were.

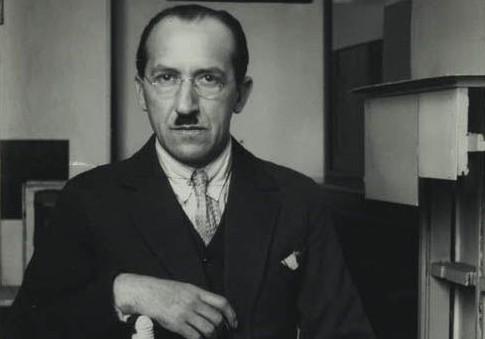

The first in-depth analysis of this enduring masterpiece was offered by the eminent art historian Erwin Panofsky in 1934. Prior scholars had generally regarded the picture as portraying an Italian merchant named Giovanni Arnolfini and his young wife, Jeanne Cenami, who were living in the Flemish city of Bruges in the early 15th century.