In writing “The Time Machine” 125 years ago, Herbert George Wells not only invented the catchphrase “time machine,” but he also invented a time machine of imagination, for its pages whisk the time-bound reader beyond the constraints of the numerical continuum of space and experience, leaping into a bizarre future that is both beautiful and brutal in its features. “The Time Machine” is both science fiction and social fiction, and as time has shown, the impossible dreams of science tend to come true, as do the impossible nightmares of society.

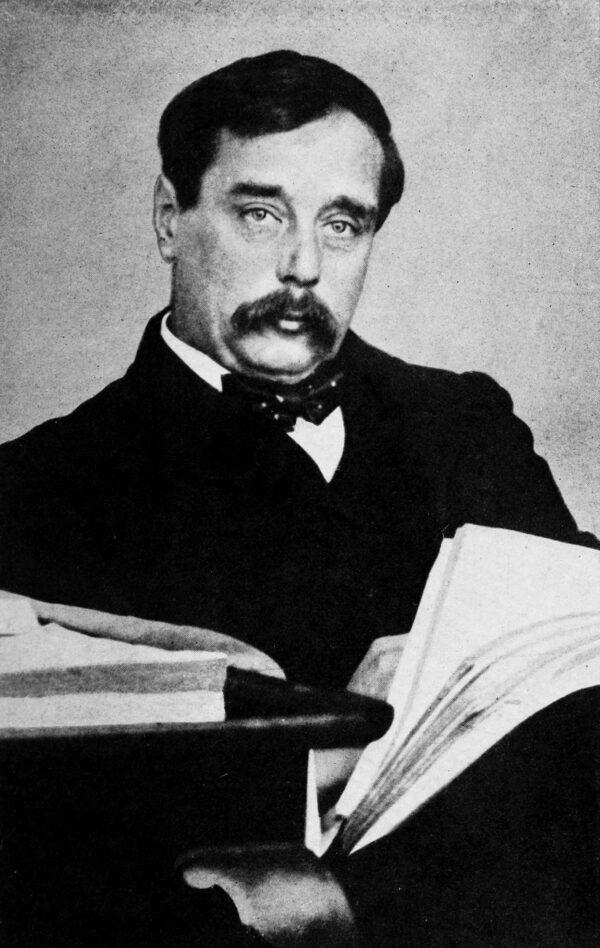

A portrait photo of English writer Herbert George Wells, circa 1918. PD-US