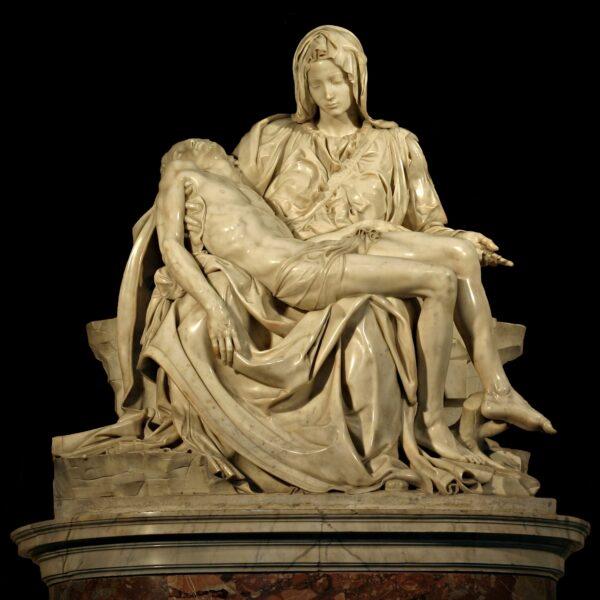

The pietà is a common theme throughout the history of Western art; it refers to a work of art that depicts the Virgin Mary with her son Jesus Christ after Jesus’s death and descent from the cross. Depicting the mother’s love for her son after he endures great suffering, the word “pietà” roughly translates to “pity” or “compassion.”

Michelangelo

“Pietà,” circa 1498 to 1499, by Michelangelo. Marble Sculpture, 68.5 inches by 76.7 inches by 27.1 inches. St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City. Image by Stanislav Traykov Public Domain