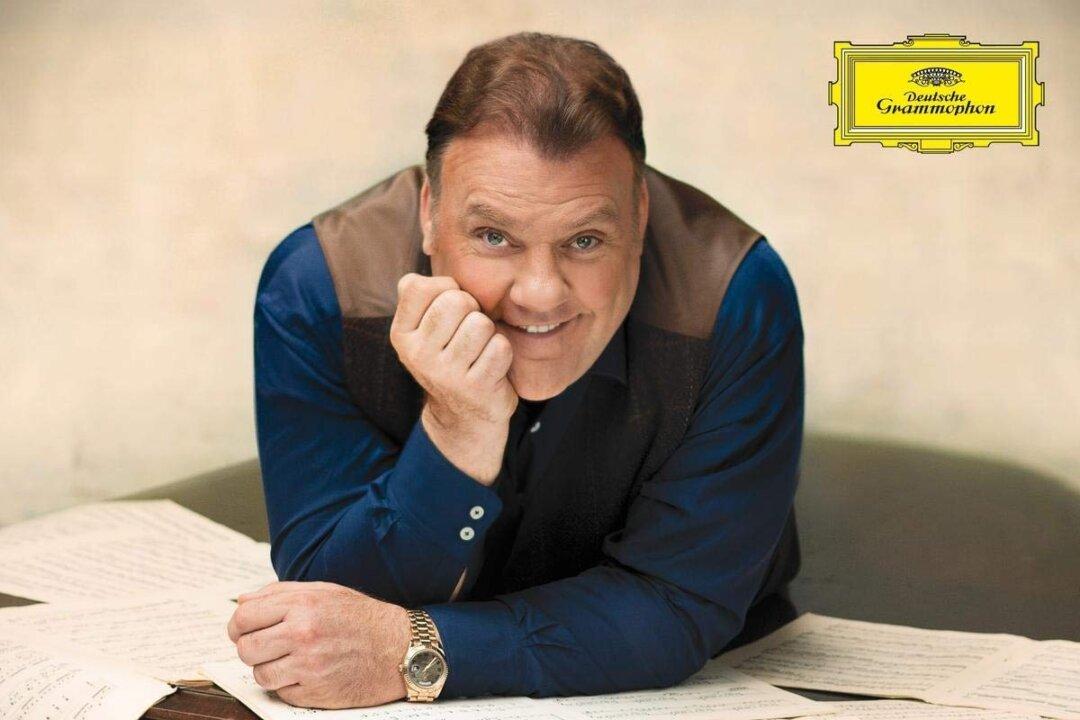

NEW YORK—The Orchestra of St. Luke’s, now in its 43rd year, began its Carnegie Hall season with Mozart’s “Great” Mass in C Minor and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1. The concert was conducted by Pablo Heras-Casado, the first conductor laureate the orchestra has appointed in its history.

The interesting idea behind the program was to present works by the two composers—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)—that do not reflect their usual style. Thus, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 is a rather conventional work, which lacks the depth and drama of his later works, while the Mozart Mass reflects those very qualities.