In this column, “The Masters’ Thread” (ept.ms/mastersthread), artists share their thoughts about how masterpieces inspire their current work.

I am trying to understand how to express the engraver’s mark in my drawings. The engraver’s mark is indelible. It’s a permanent statement of intent. The artist has one shot at getting each mark right—it cannot be retracted or erased. This type of mark-making, found in engravings and etchings, can also be applied to any other drawing medium. I think of the engraver’s mark as being more connected to a certain state of mind than to a specific medium. These are marks that indicate bold and instinctive statements.

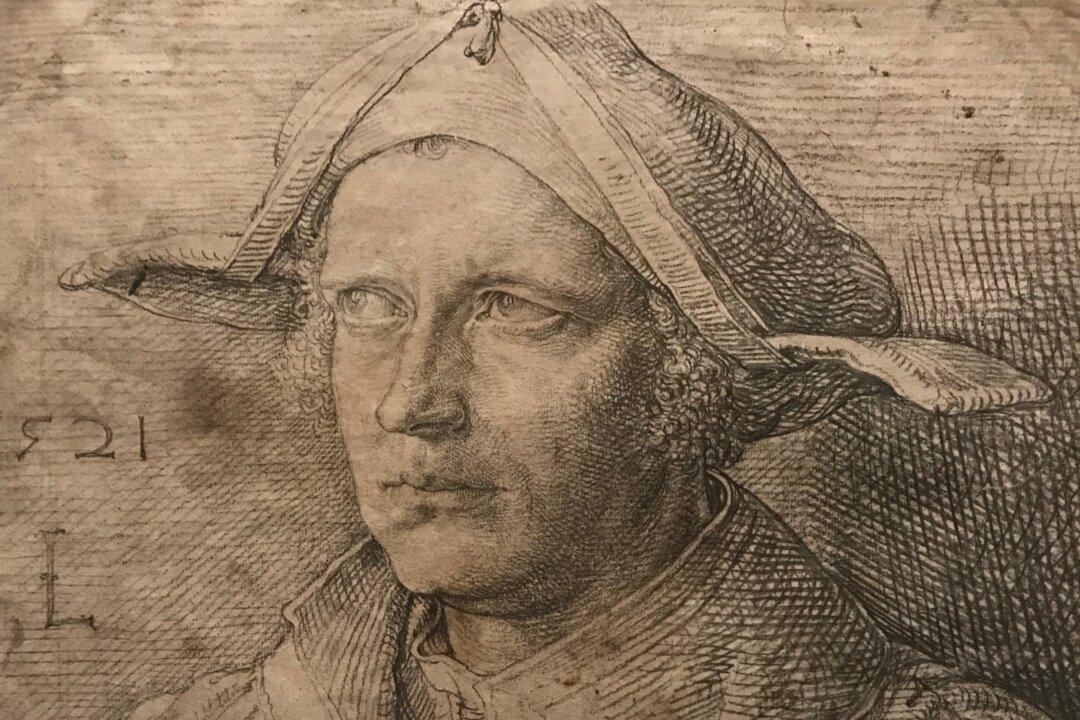

The Albrecht Dürer drawing “Portrait of a Young Woman with Braided Hair” and the Lucas van Leyden drawing “Portrait of a Man with a Cast in His Eyes” at a Morgan Library & Museum exhibit ("Treasures from the Nationalmuseum of Sweden: The Collections of Count Tessin,” on view until May 14) resonate with me as I have been looking to German and Dutch draftsmen for inspiration lately.

In my recent work, a self-portrait, I attempt to mimic the engraver’s mark by using direct, fluid lines applied with gouache, ink, graphite, and charcoal. The lines of white gouache follow the topography of the illuminated side of my face, giving it a graphic, linear quality. I applied an ink wash with charcoal behind my head to give contrast and tenebrism [a style of painting initiated by Caravaggio]. I expressed the form by using open hatch marks, leaving the exposed paper underneath as halftones. Because this is a multimedia drawing, it has a textural quality, which I intended. This drawing was heavily influenced by Käthe Kollwitz, my favorite German female artist. I made it three months after giving birth to my daughter.

My ink drawing “Eve Sleeping” was created around the same time as my self-portrait. It was made with walnut ink, a nib, and a small brush. I use ink as a medium for drawing, as it challenges me to make bold statements and to live in the moment with each mark. Ink can be hard to control at times, so it has an element of surprise. This makes the process very intriguing to me because of its potential for happy accidents. Yet it leads to many failed attempts.