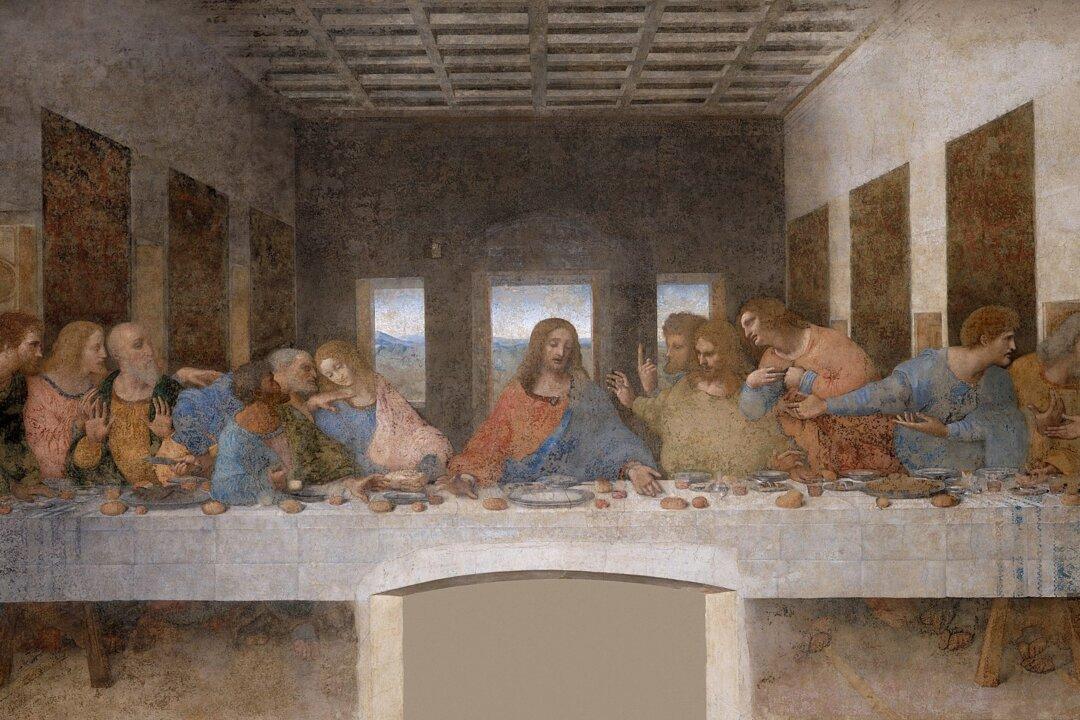

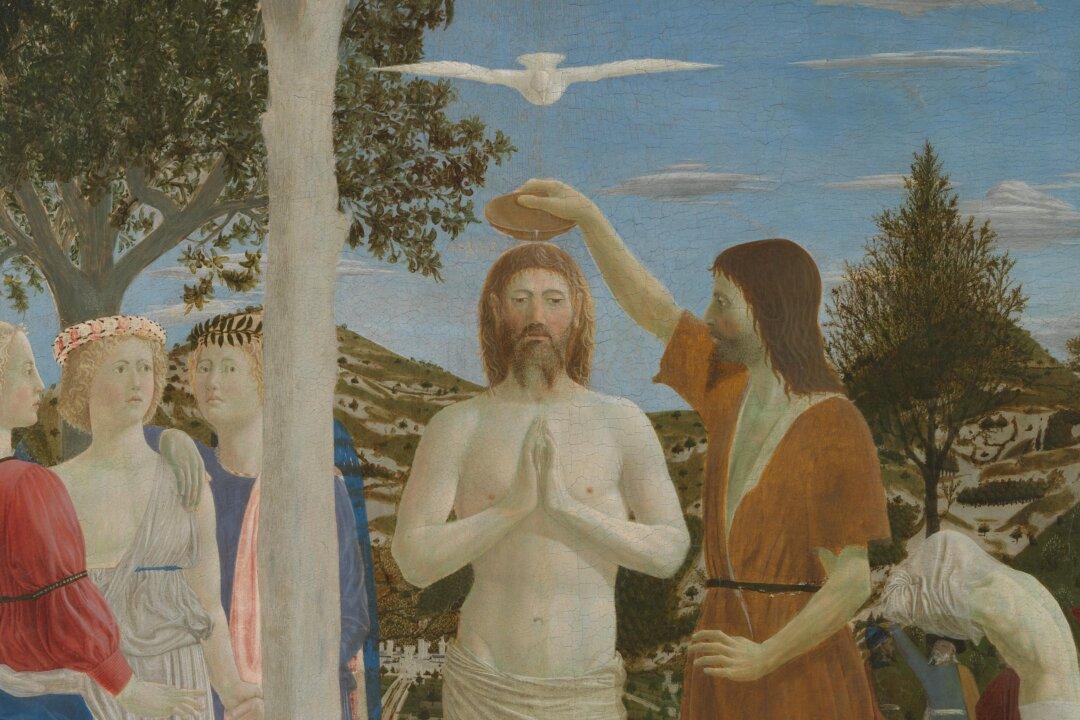

Some paintings almost everyone in the Western world knows: Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa,” Piero della Francesca’s “The Baptism of Christ,” and “The Night Watch” by Rembrandt van Rijn. They are part of the West’s visual vernacular. These are the images we see on tea towels, t-shirts, cellphone covers, and fridge magnets.

The name Rembrandt has become a synonym for greatness. There are Rembrandt restaurants, Rembrandt hotels, and even Rembrandt toothpaste.