Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, seven miles south of Monterey, California, is one of the most gorgeous spots on the West Coast. Though the underwater preserve comprises more than 9,907 acres, the land open to the public is surprisingly compact—just 400 acres bordered by a six-mile perimeter trail. However, this meeting of land and water contains stunning views, a diverse range of animals and plants, and a fascinating cultural history.

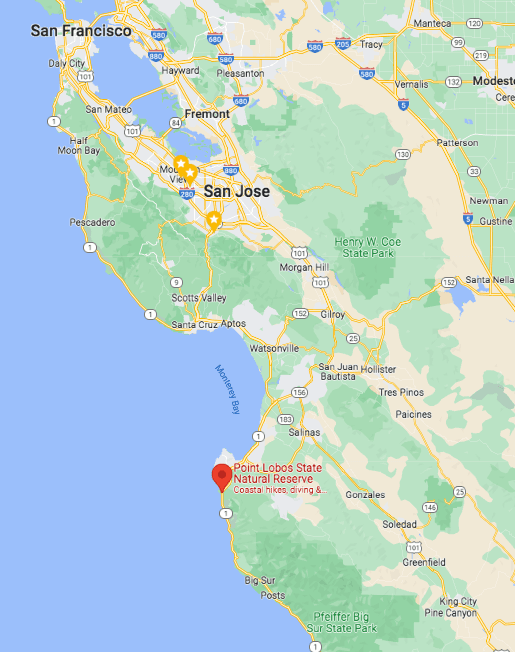

Map of Central California showing Point Lobos Reserve. courtesy of Google Maps