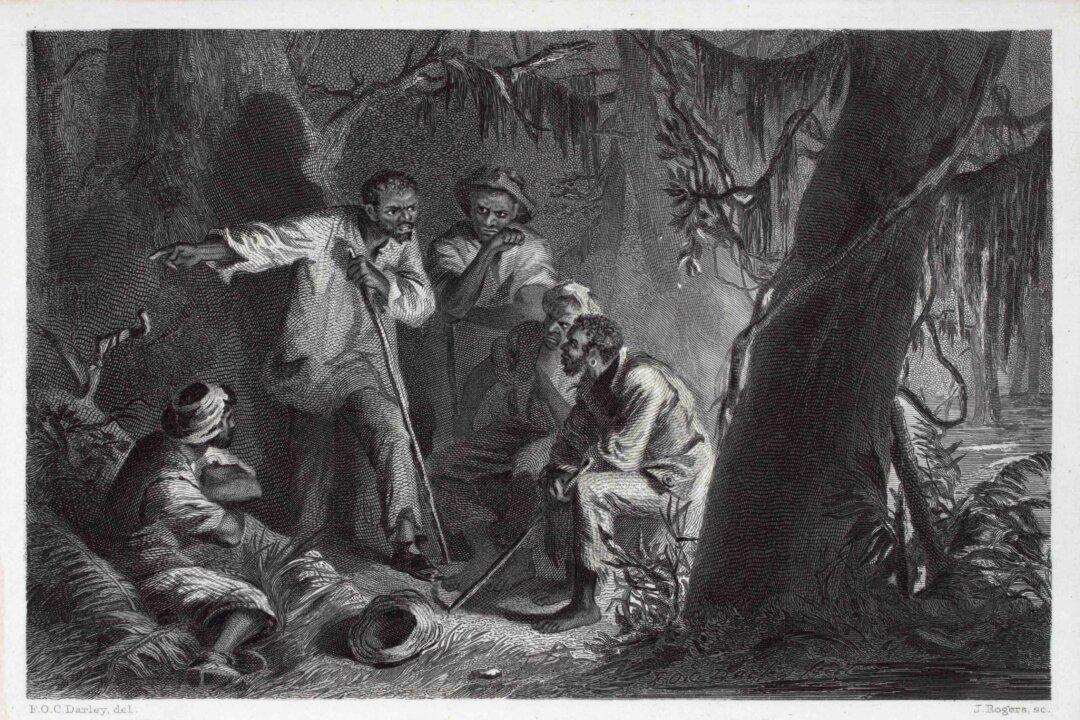

Decoys originate from man’s efforts to lure waterfowl. Whether hunting with nets, traps, or firearms, hunters came to value decoys as highly as boats, blinds, and shotguns. As weaponry improved and populations increased in the latter part of the 19th century, more and more people hunted waterfowl for food and sport, and the demand for decoys grew. The art of the decoy entailed that the fabrications should appear lifelike from afar—the more realistic the decoys, the more successful the hunt.

The waterfowl decoy is now a treasured form of folk art. Often highly sought after as collectibles, many are quite valuable. From old working decoys to the modernized, stylized, and finely carved, they reflect the impact of technology, environment, society, and economy on an American way of life.