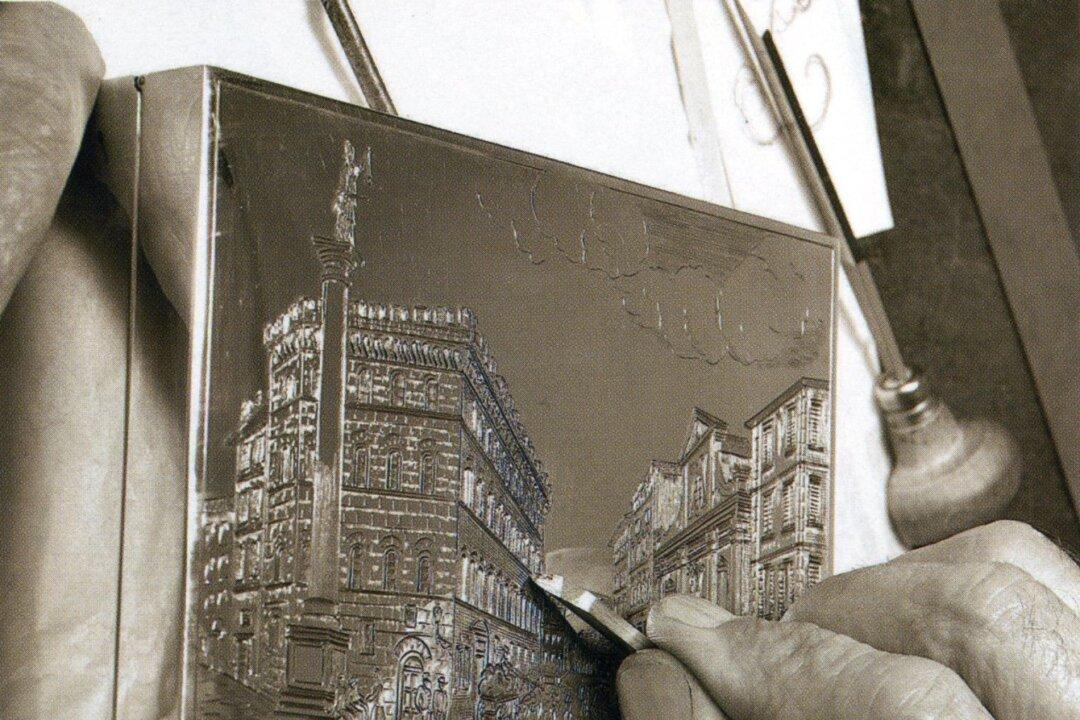

FLORENCE, Italy—If your idea of silverware is mere platters and other flatware such as forks, knives, and spoons, you are in for a treat: Argentiere Pagliai’s collection showcases the pure artistry of a traditional silversmith.

Since 1947, Argentiere Pagliai has made high-end precious metal pieces inspired by the traditional arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. The company continues to create with incredible passion and to uphold the silversmith tradition that is endangered across Europe. Those who specialize in silver restoration, in particular, are only a handful.