When you think of the Renaissance, you likely first think of Michelangelo or da Vinci, perhaps the Golden Ratio, and one city in particular—Florence. But what you may not know is that artisans to the north were in many ways setting a standard that their Southern European brethren would covet and emulate.

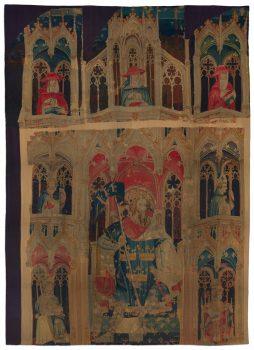

“King Arthur (from the Nine Heroes Tapestries),” circa 1400. Munsey Fund, 1932; gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1947. The Metropolitan Museum of Art