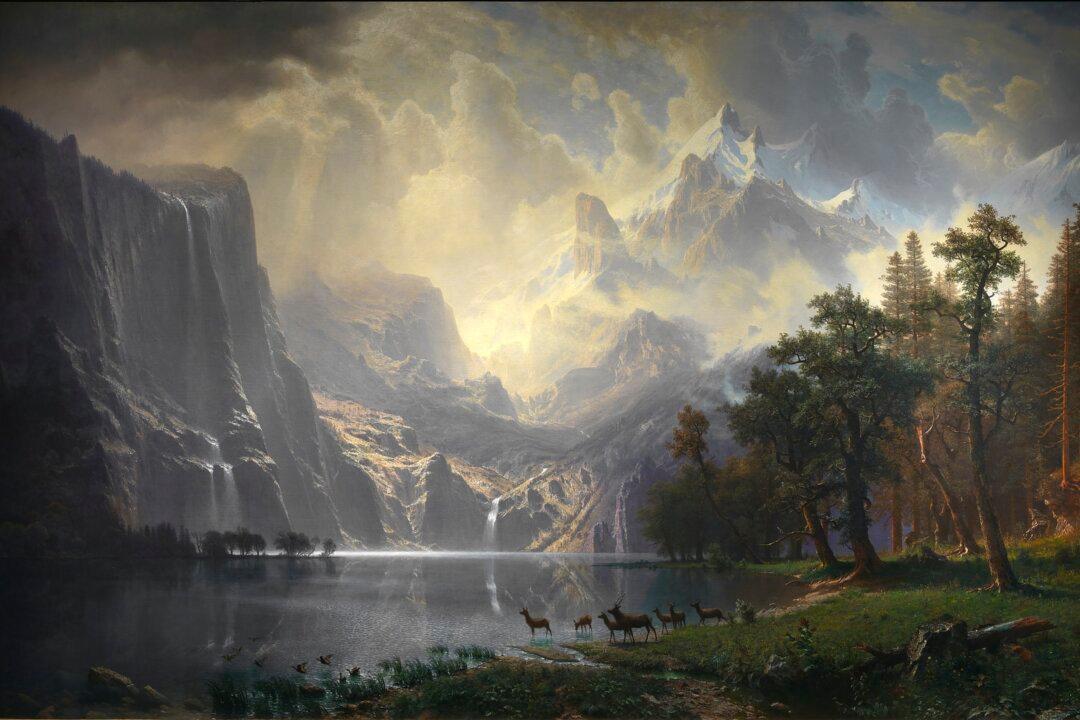

For years, I wrote only about what piqued my interest. In discussing art—paintings and sculpture—it was either pieces I had purchased and displayed in my home, or those I bid on unsuccessfully. Always, the interest was self-generated.

Then something different happened. I was provided several links to websites with paintings and asked if I could write about one of them. Would any of these stir my senses? The odds seemed against it; how particular I thought my taste to be.