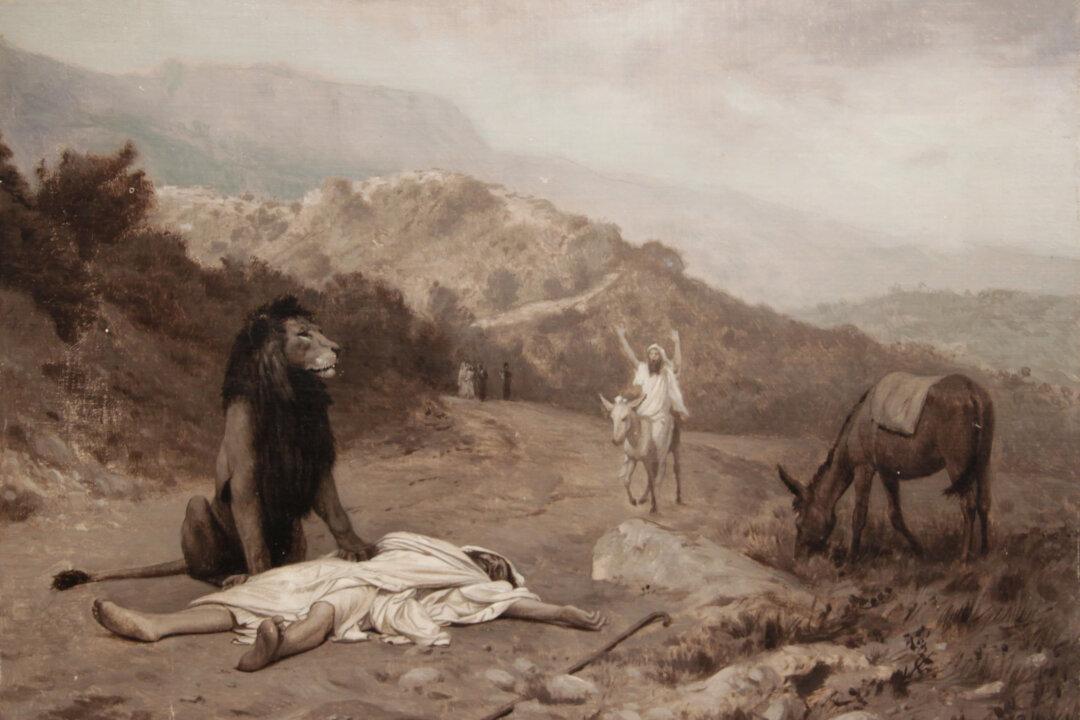

The story of the disobedient prophet is told in the Bible in the book of 1 Kings. The story goes as follows:

A man of God traveled from Judah to Bethel. God spoke through him and cursed an altar where King Jeroboam made an offering. Jeroboam ordered the man of God to be arrested, but Jeroboam’s hand shriveled up when he pointed to identify him.