I am actually still shaking. I just listened to Beethoven’s “Fifth Symphony”—again—and it is simply apocalyptic! The fantastical, audacious bombast elicits an almost nervous laughter. It is thrilling and enthralling, truly and utterly stunning—the signature work of a singular man, a man with visionary clarity and absolutely zero time for ambiguity. That man is Ludwig van Beethoven.

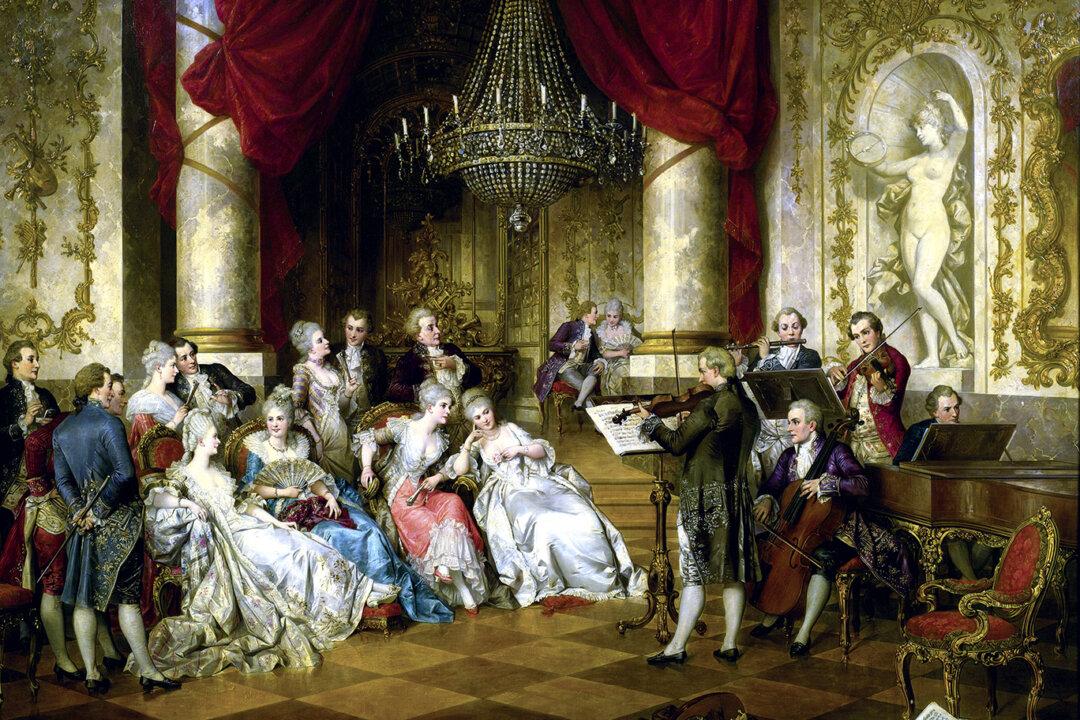

It is almost impossible to think of Beethoven and not mention Mozart. While Beethoven was certainly following in Mozart’s footsteps, he was unquestionably charting his own very distinctive course. A brief comparison of these two giants might be really useful in understanding who Beethoven was.