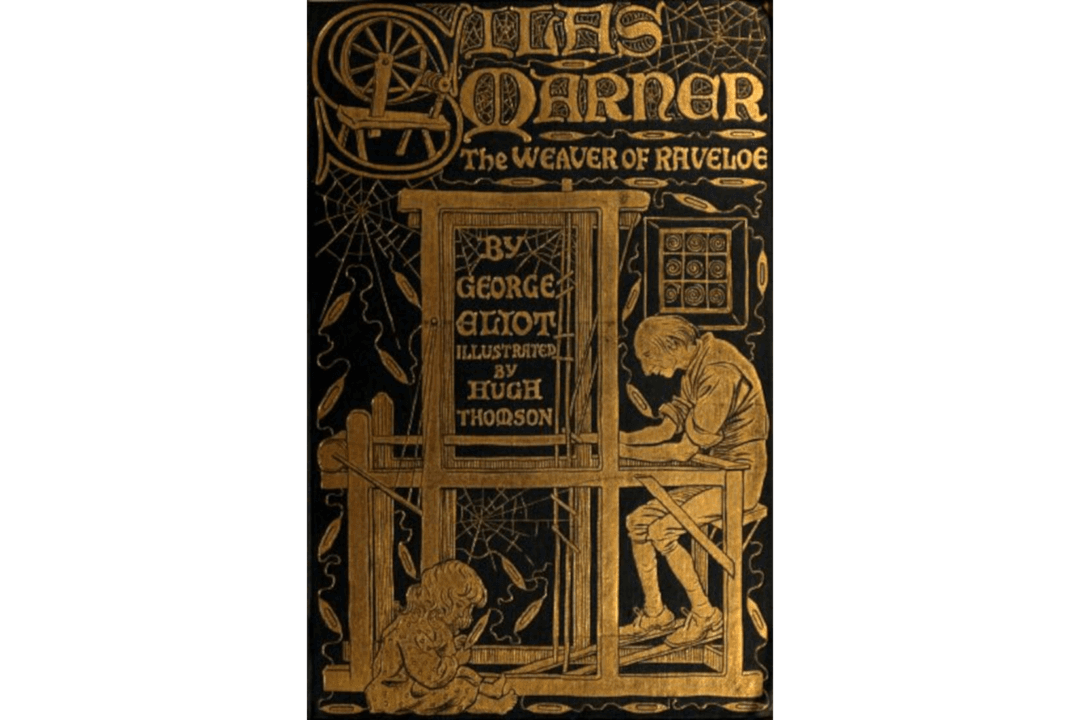

Falsely accused of taking money from his church—the real thief is his best friend, who sets him up and marries his fiancée in the bargain—the weaver Silas Marner leaves behind his job and acquaintances at Northern England’s Lantern Yard. He moves to the remote village of Raveloe in the Midlands, where he sets up his loom. For 15 years, he plies his trade there, having little to do with his neighbors or the local church, brokenhearted as he is by the betrayal of those whom he had trusted.

In Raveloe, Marner gains a reputation for being both a miser and a sort of freak. His bulging eyes and scowling countenance frighten the young children who peep through the windows of his cottage. His catalepsy causes him to fall into a trance at times (unable to move and unaware of what is occurring around him), which leads the villagers to be wary of him, with some wondering whether he is an instrument of the Devil. As he makes money from his exquisite skill at the loom, he forms the habit of nightly counting his gold and silver coins.