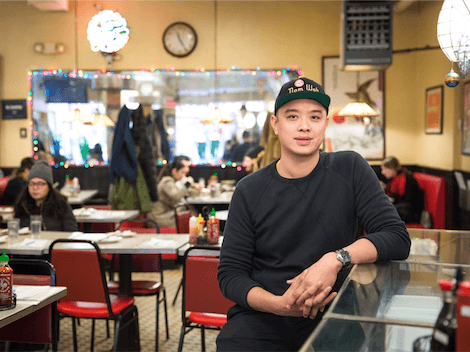

In Manhattan’s Chinatown, a foodie paradise brimming with scrumptious noodles and mouthwatering dumplings, perhaps no establishment is as legendary as the Nom Wah Tea Parlor. Almost a century ago, Nom Wah was the first dim sum parlor to open in New York City. Since Nom Wah’s relaunch in 2011, flocks of restaurant-goers congregate outside every day, awaiting a taste of Nom Wah’s famed dim sum offerings, from its original “OG” egg rolls to its classic shrimp dumplings.

Wilson Tang, Nom Wah’s current owner, is a towering figure with a friendly, youthful face. Although Wilson grew up in a family of restaurateurs, his Chinese immigrant parents despised the idea of their son working in a restaurant. “‘We do not want you in the restaurant at all. Stay far, far away.’ And I think that’s the immigrant’s mindset,” Wilson said. Toiling away at multiple jobs, they hoped Wilson would end up in a comfortable and stable white-collar position.