As human beings living in this world, we are often bombarded with materialistic desires that may fuel our sufferings. We can be led to believe that our lives would be better if we only had more—more money, more affection, more education, more beauty, and so on. Pursuing more, however, often leads to more hardship.

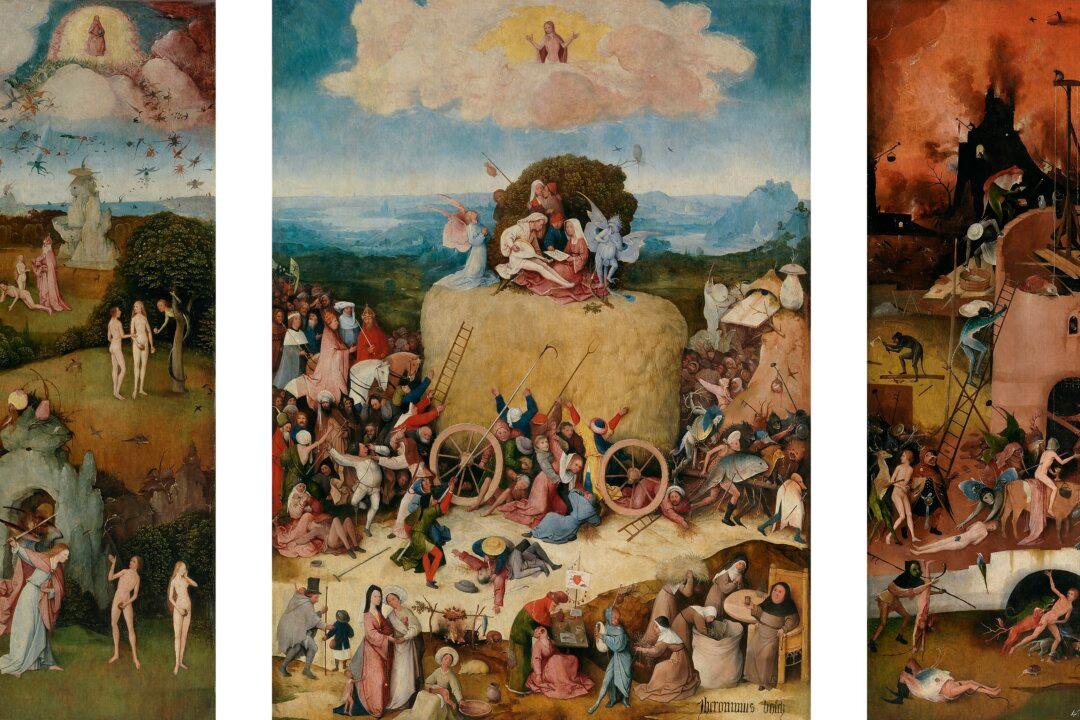

For me, Hieronymous Bosch’s painting “The Hay Wagon” reminds us that we increase our sufferings when we pursue materialism and ignore the divine.