Before she passed away this June, Martha Erlebacher was a prolific artist and demanding teacher. The New York Academy of Art is holding her first ever retrospective.

NEW YORK—Here’s a hypothetical situation so familiar it’s almost cliché: Two people stroll through an art gallery, stopping to consider one avant garde object after another. One of them has been laboriously serving up analysis to his friend, who offers little in return but the occasional “uh-huh” tinged with skepticism.

They come to a Modern painting, all squiggles and splatters. The unimpressed one is chafing, and it’s starting to show.

“I could have done that,” he mutters.

“Sure. But you didn’t,” the other retorts in exasperation, launching into another explanatory attempt, which we will relinquish to their hypothetical world.

This month in the real world, we are invited to acquaint ourselves with a woman who could do that, and did.

Throughout her 45-year career, Martha Erlebacher produced at least 800 paintings, both abstract and figurative. A small number mostly from the last 15 years of her life are now showing at the New York Academy of Art (NYAA) in the first ever Martha Erlebacher retrospective.

Jab and Roast

Before she passed away from ovarian cancer this June, one of her last projects was a series of paintings in the style of artists like Picasso, Robert Indiana, Cy Twombly, Matthew Barney, Jasper Johns, Chuck Close—except she inserted the theme of a duck in all the pieces, as parody or as homage, or both.

Why a duck? Nobody knows for sure, but it seemed to have started with a goofy little porcelain one she used in a still life.

The appearance of the Avant Duck Series at the end of her career demonstrates her caustic wit and highlights the amazing path she blazed.

Erlebacher trained as an artist in the ‘60s, when abstract expressionism was de rigeur and figurative art instruction hard to come by. But she loved Renaissance works, so she taught herself how to render the human form, a process that involved analyzing bones, muscles, and sinew.

She, her artist husband Walter, and the circle of Philip Pearlstein and Alex Katz formed a group of modern artists who pushed the contemporary figurative art movement in America. Together they spurred the founding of the NYAA, one of the city’s most esteemed teaching institutions dedicated to anatomy.

Complex Personality

Petite, intense, and unyielding in her beliefs, Erlebacher taught at the NYAA between 1992 and 2006, becoming a beloved if somewhat feared instructor. “Grown men would be in tears” after her critiques, said Peter Drake, the graduate school’s dean of academic affairs.

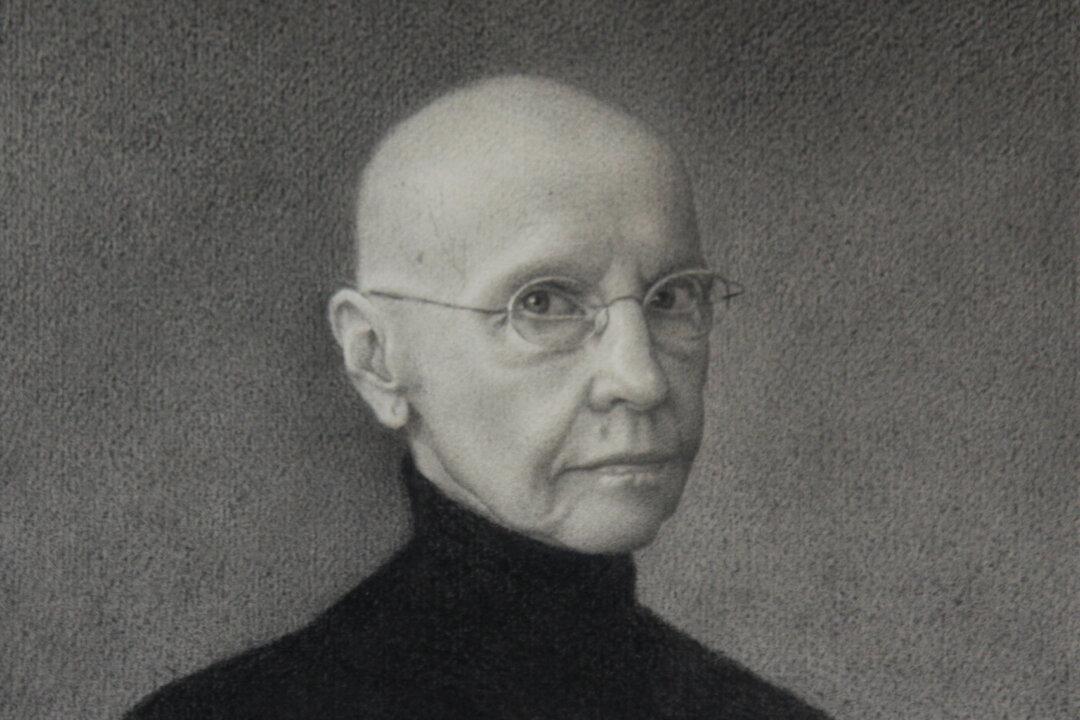

A small self portrait in pencil hangs in the beginning of the gallery. She wears a simple black turtleneck and wire-rimmed frames. Her hair is obliterated by chemotherapy, but her gaze still pierces.

Harvey Citron, head of NYAA’s sculpture department, was friends with Erlebacher since the ‘60s.

“She was an enormously ethical person,” Citron said. “She could not be moved off a point that she believed in, she demanded loyalty, anyone who lied to her she would have nothing to do with. And she was extraordinarily hardworking.”

Range of Works

“Apollo,” 1971, is the earliest work in the retrospective. It’s clear from the topic and and the way of shading of the body that she referenced Renaissance work. It’s also clear to a trained eye that Erlebacher created it before she fully mastered the human form—the shins are a bit short, the waist a bit high. The son of Zeus looks a bit downcast placed in an art deco setting.

The rest of the works show a greater level of maturity. The cycle of life is a recurring theme in her work.

In the 2006 studio work “The Cycle of Life, Fire, Youth,” four young nudes lounge at the beach atop a satin-draped pedestal. She cleverly uses the figures’ postures to create a closed loop in which the eye travels, and uses their bent limbs to creates visual rhythm.

Erlebacher was known primarily for her figurative work but her still-lifes are superb. This exhibition is graced with several paintings of pluck-them-off-the-canvas fruit.

“She saw them as allegories as much as the figurative pieces were...There’s a kind of somber, melancholic quality to them,” Drake said.

She became so adept at still-lifes, her sons said she could complete one a week on top of her full time teaching, according to Drake.

Challenges in Self Education

When Erlebacher taught herself anatomy in the early 60s, it was an uphill battle.

“At the time she was working in an environment where there was almost no support for this and it was very marginalized—either you were doing pop art or minimalist,” Drake said. “Now if you were a young artist trying to teach yourself, there'd be other people you could refer to.”

That’s partially thanks to Erlebacher’s conviction that direct observation, understanding of light and shade, color, and perspective are fundamental to an artist’s work.

Just a month before she passed away, Erlebacher appeared in a video interview for the 2013 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, in which she won the title of commended artist for her self portrait.

“It was essentially the bald head that got me—I was interested in studying the form of my head, essentially,” she said, grinning. “What I find the most fun is to look at something and replicate it and copy it—something that’s out there and make a two-dimensional image of it,” she said.

Martha Erlebacher Retrospective

Nov. 5–24, daily 2–8 p.m. or by appointment

Closed Wednesdays and holidays

New York Academy of Art

111 Franklin Street

212-842-5966

nyaa.edu; free