“The road to hell is paved with good intentions” is a common expression. Having good intentions is, of course, better than harboring malicious ones, but who hasn’t caused a mess at one point in their life, despite their good intentions? Good intentions don’t always yield good results, nor are they necessarily truly good.

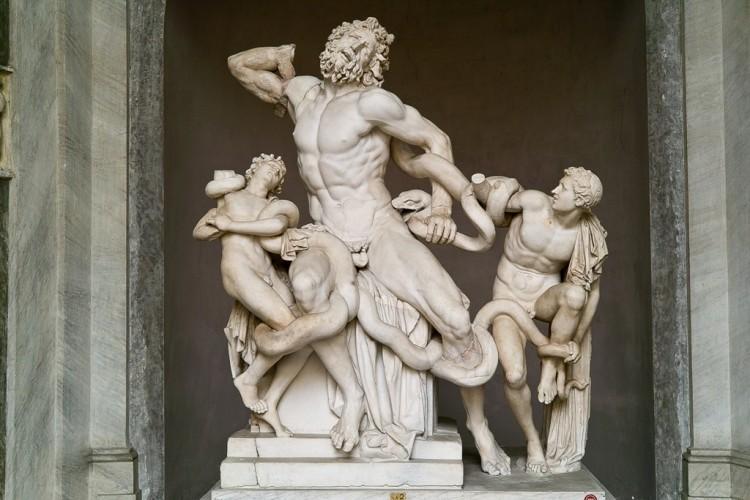

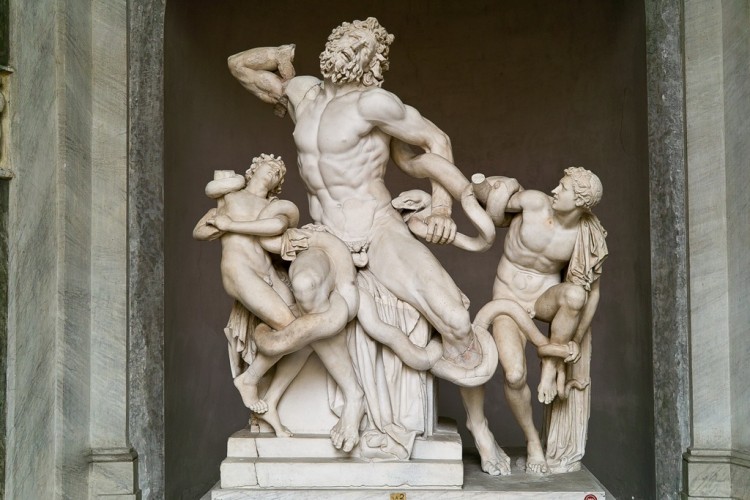

What is the story behind this sculpture? After years of war, the Greeks came up with the cunning plan to hide their troops in a huge wooden horse outside Troy and had Sinon, a Greek spy, convince the Trojans that the horse had magical powers.

The suspicious Trojan priest Laocoön, however, tried his utmost to persuade his fellow citizens to burn the horse. Suddenly he was struck with blindness. As he continued to try to persuade his brethren, one of the Greek gods (according to different versions of the story, this deity could be either Athena, Apollo, or Poseidon) summoned a handful of deadly sea serpents to devour Laocoön and his two sons.