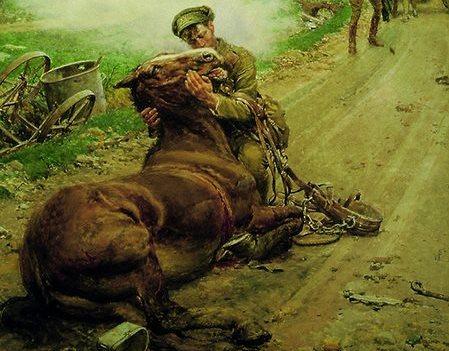

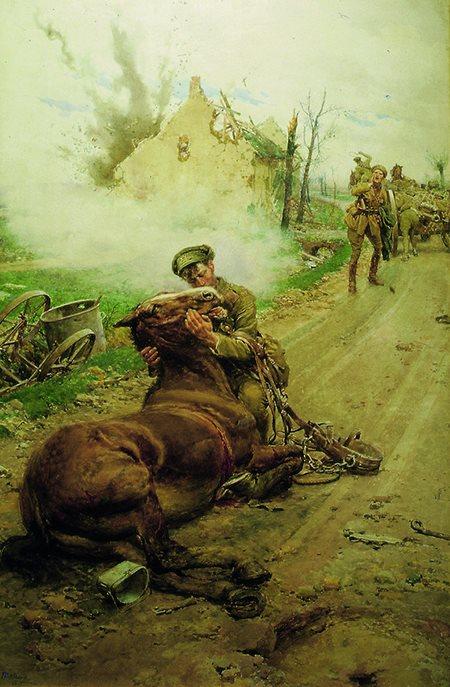

“Goodbye Old Man,” 1916, Fortunino Matania. Watercolor. Blue Cross Animal Hospital, Victoria, London. Public Domain

Given that the recent days have been rightfully occupied by the remembering of the humans who never made it home from World War I, I thought I might highlight a less represented species, many of whom also never made it home from that war.