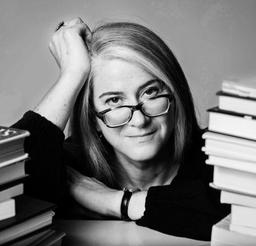

NEW YORK—Hélène Grimaud can look straight into your eyes with an intensity that is arresting. Her gaze has a certain wildness and unwavering quality that matches the passion with which she plays the piano.

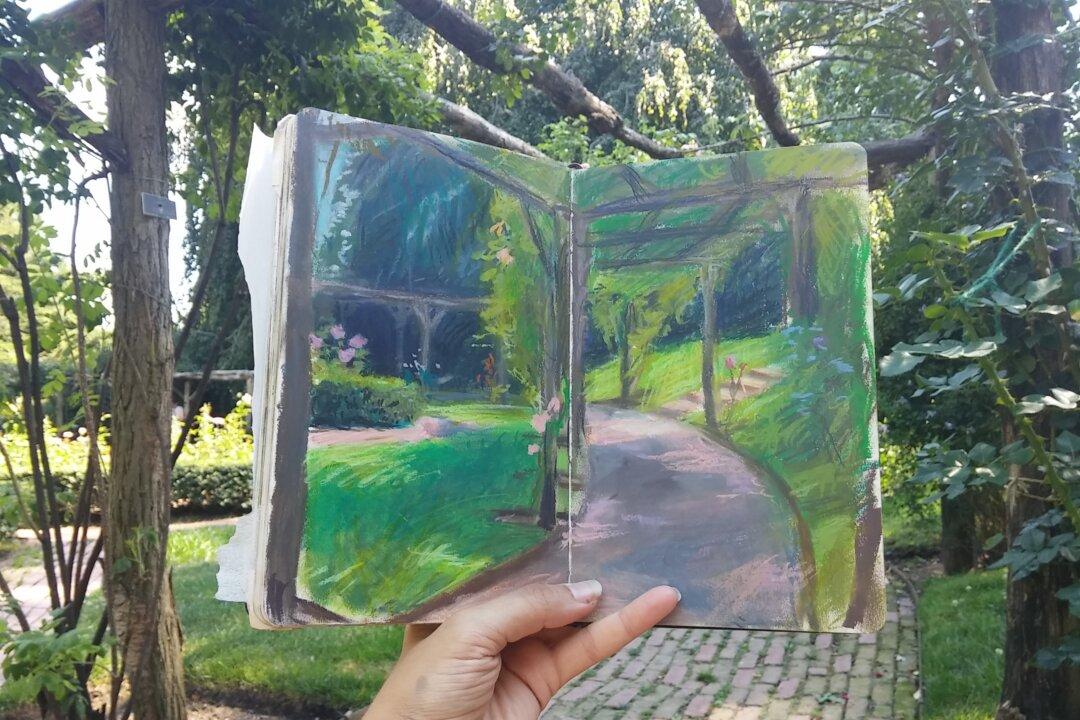

Nature is her ultimate muse. “I always felt a strong sense of the sacred being in wild spaces,” she said at the Mandarin Oriental hotel on Feb. 9, during her publicity run of interviews and photo shoots with various media.

A highly celebrated pianist in the world today, Grimaud is also a dedicated wildlife conservationist, a writer, and a human rights activist. Born in Aix-en-Provence, France, she feels more at home in the United States. After living in Switzerland for some years, she just recently returned to live in upstate New York near the Wolf Conservation Center that she founded in 1999. “I knew I was going to come back, so it was only a matter of when, not if,” she said.

The environmental education organization takes care of four ambassador wolves—wolves raised from puppies by humans, never to be released into the wild, to help educate the public about their endangered counterparts. The Wolf Conservation Center also participates in the Species Survival Plan (SSP) for the Mexican gray wolf and the red wolf.

Nature as Muse

Hiking through woods, up mountains, or being anywhere in nature is the best place for Grimaud to slow down, be quiet, and start listening. “You have no choice then but to fill that space. That’s when things start to develop, and the imagination starts to blossom,” she said.

In line with her affinity with the German romantic movement’s precept of the artist penetrating the depths of creativity through a communion with nature, Grimaud bridges two worlds like an ambassador wolf. “When you are on stage there is that wonderful aspect of being like a medium, in the literal sense of the word, where you are this open channel that connects the world of the audience to the world of the composer. … It’s a great responsibility but it is also something very liberating,” she said.

Grimaud feels freest when she is performing in a great space with optimal conditions. “There is nothing like that to help you take off and just fly to another dimension,” she said. But she hardly ever feels at ease wearing dresses during performances or at any other time. “I’m always happier to just go on stage wearing a slight variation of a pajama kind of outfit,” she said, laughing.

Sometimes when she plays the piano or listens to music, she experiences the sounds in color. Her synesthesia is consistent. For her, D minor is always dark blue, C minor is always black, G is green, F is red, and B flat is yellow. “The color changes with every modulation in the piece, but the dominant color is the one of the tonality in which the piece is written,” she said. It doesn’t happen every time she plays or listens to music, and it doesn’t necessarily help her memorize the music, “but it’s nevertheless a beautiful thing to be experiencing,” she said.