Photos and Paintings Track Medieval Icelandic Sagas in Manhattan Exhibit

A new exhibit at Scandinavia House tiptoes across the centuries to make ancient tales vividly come to life.

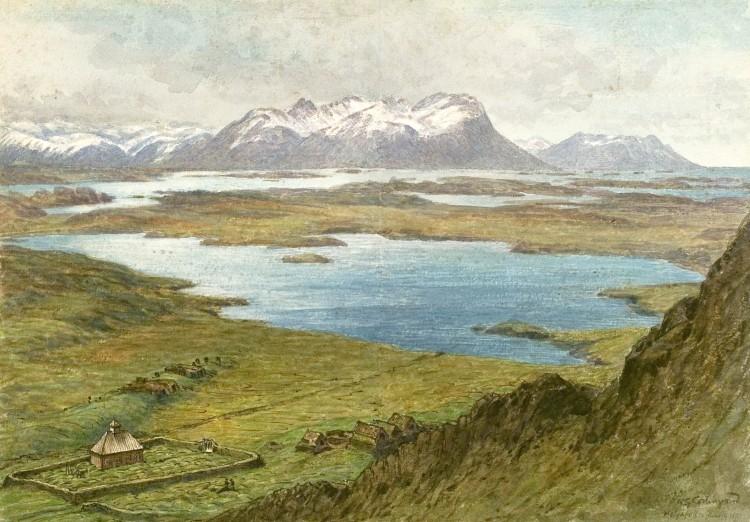

W.G. Collingwood’s 1897 watercolor painting “From Mt. Helgafell.” Courtesy of the National Museum of Island

|Updated: