Two extremes predominate in writing about the great composers: a tendency to romanticize and mythologize them into inspired demigods, and the current tendency to pull their statues down from their pedestals or perhaps their little composer busts from our pianos. This second view focuses on all of their human flaws, whether real or imagined on scant evidence. One thing is usually above guesswork, though, the concrete historical record in things such as birth certificates, deeds, and lawsuits.

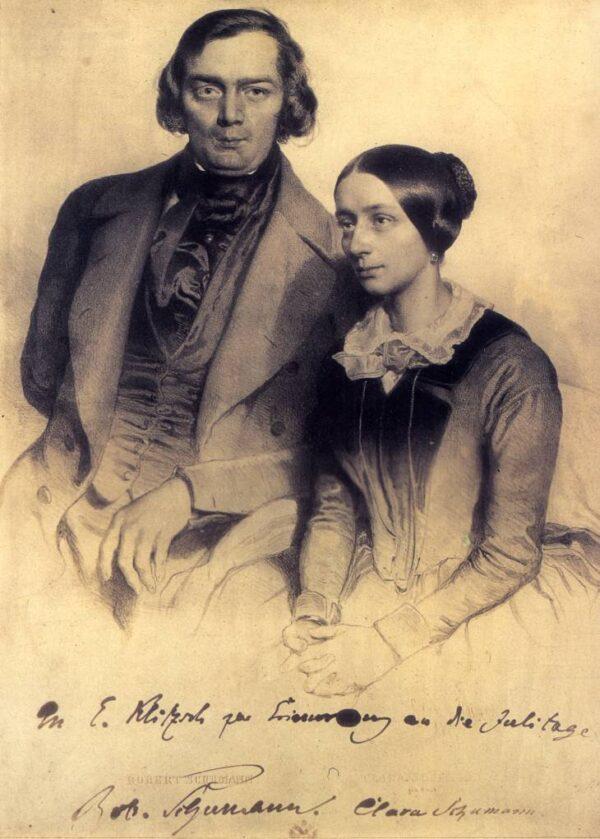

An 1847 lithograph of Robert and Clara Schumann. Public Domain