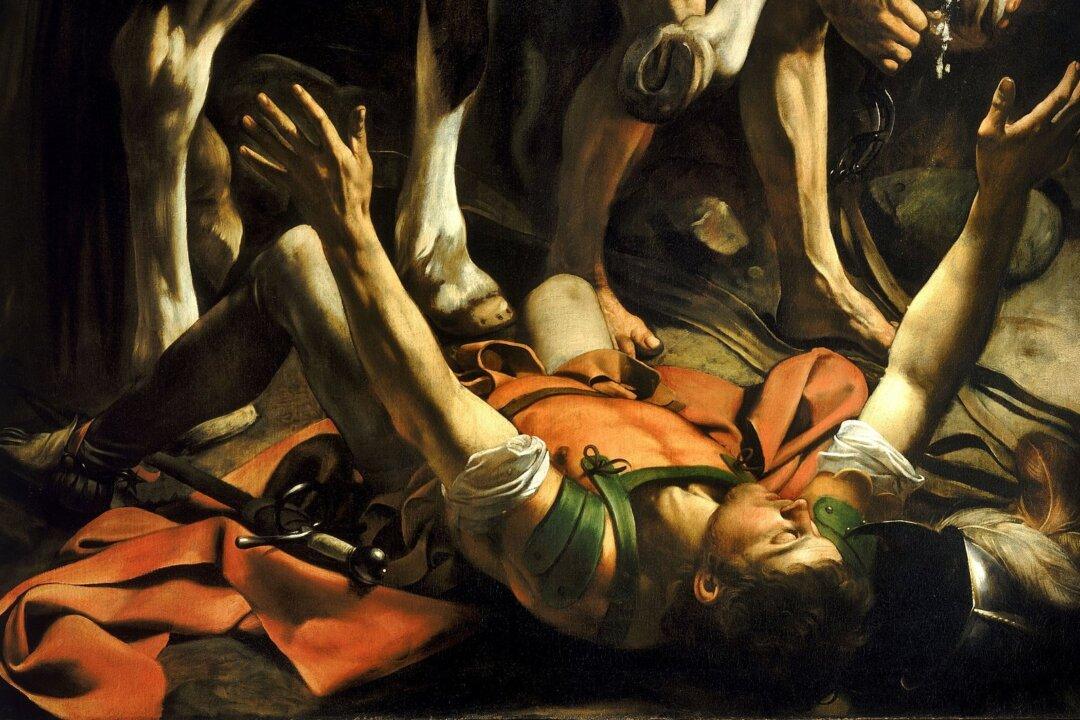

In 1600, Caravaggio, an Italian Baroque painter of biblical scenes, was commissioned by Tiberio Cerasi to paint a scene of Paul’s conversion on the way to Damascus.

Saul’s Conversion

Saul of Tarsus, who would later be called Paul upon his conversion to Christianity, was a Jew from Asia Minor and a member of a religious sect called the Pharisees. As a Pharisee, Saul believed in life after death and in the significance of Jewish traditions, and he carefully studied the Hebrew Bible.For the first half of his life, Saul persecuted adherents of the then-new religious movement Christianity. Scholars say there’s no evidence that his attempt to persecute Christians stemmed from being a Pharisee, but Saul may have believed that converts to Christianity were not respectful of Jewish traditions and mingled too freely with the non-Jewish.