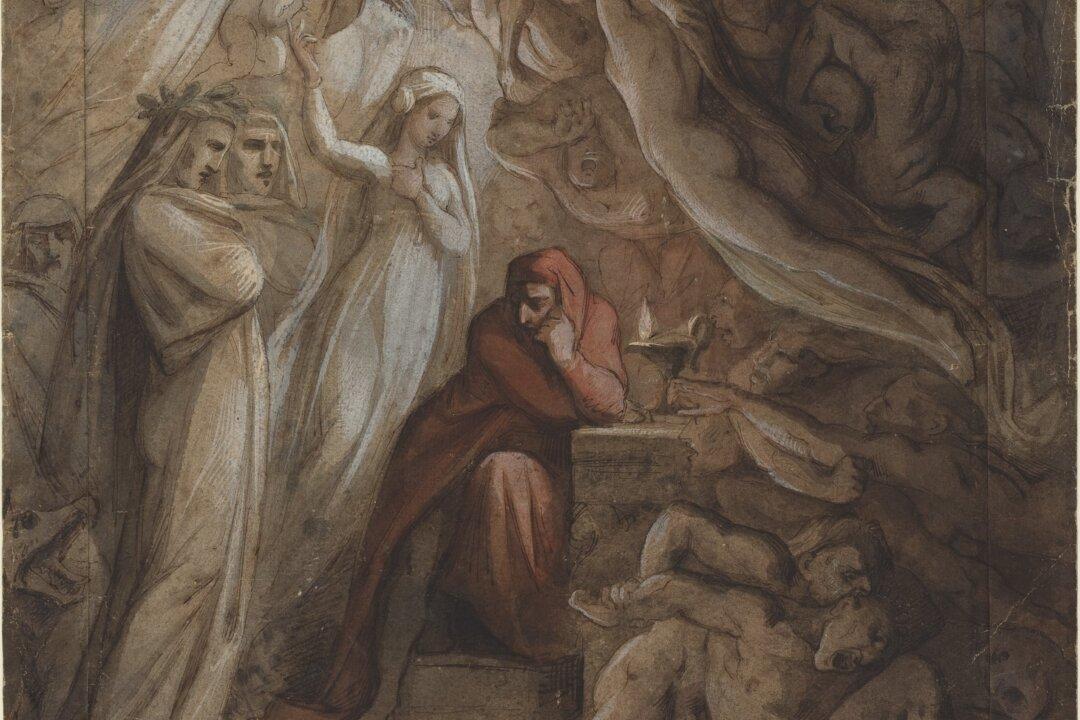

Where are we heading—heaven or hell? Poet Dante Alighieri explores that question in his epic poem “The Divine Comedy,” which he completed in the year that he died, 1321.

Dante wrote 100 cantos (sections), averaging 142 lines, for his poem that charts the journey of the pilgrim Dante through hell to purgatory and paradise. The ancient Roman poet Virgil, symbolizing human knowledge, guides Dante through hell and purgatory. And Dante’s childhood love Beatrice, representing the divine mysteries, guides the pilgrim from the top of the mountain of Purgatory (the Garden of Eden) to Paradise. St. Bernard of Clairvaux guides Dante through the Empyrean, the highest levels of heaven, to see God and the souls of those who have been saved.