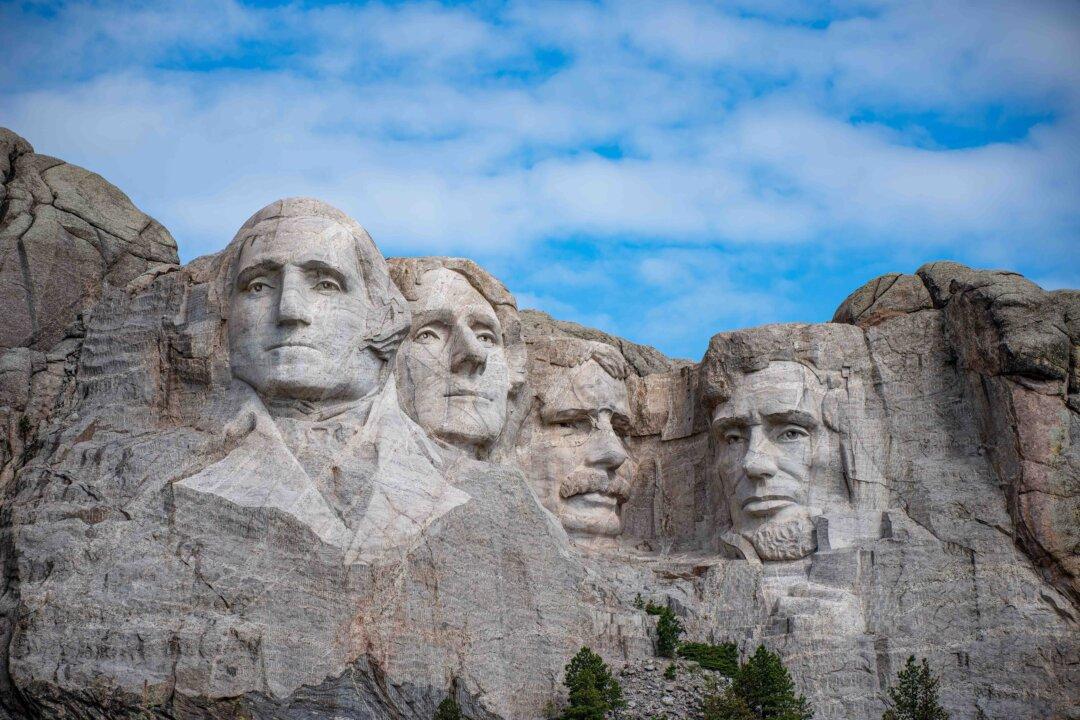

A plane buzzed over the Black Hills of South Dakota in the summer of 1927. It swooped and dove through the air, entertaining President Calvin Coolidge and his family below. The pilot dropped a wreath of flowers to this little crowd and sped away.

The Coolidges had chosen the large Game Lodge in Custer State Park as their summer retreat, where they tried to keep a quiet schedule. However, an ambitious sculptor nearby had other ideas.