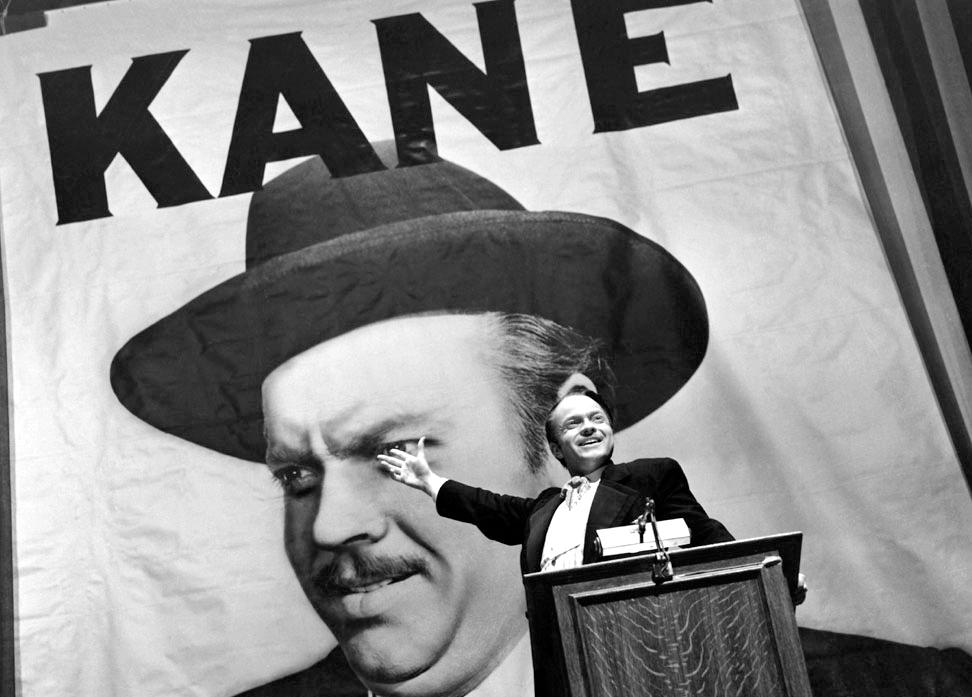

“Rosebud.” What picture does that word bring to your mind? You may be thinking about a gift on Valentine’s Day, but this particular blossom gained a new meaning 80 years ago. “Citizen Kane,” Orson Welles’s 1941 masterpiece, begins with the titular character gasping “Rosebud” before dying. The rest of the film is a series of flashbacks from different people’s perspectives, chronicling a reporter’s quest to uncover the secret of Kane’s dying words.

The American Film Institute lists “Citizen Kane” as No. 1 on its “100 Years…100 Movies” list, but many people haven’t watched this classic. Last year, Netflix Inc. revived the dramatic story of a newspaperman who gains the whole world and then loses it in his quest for public adoration.