In the very heart of the Mediterranean Sea lies the tiny archipelago of Malta with its mysterious 7,000-year-old history.

The first people to arrive on the Maltese Islands were thought to be from southern Sicily, its closest neighbour. It’s just a theory, since the megalithic structures built by these Neolithic adventurers bear no resemblance to Sicilian culture … that is, none that has so far been discovered.

The mystery surrounding the original settlers is yet to be revealed, but regardless, all who travel to Malta and gaze in wonder at what these ancient peoples accomplished cannot help but be awed by the legacy in stone they left behind.

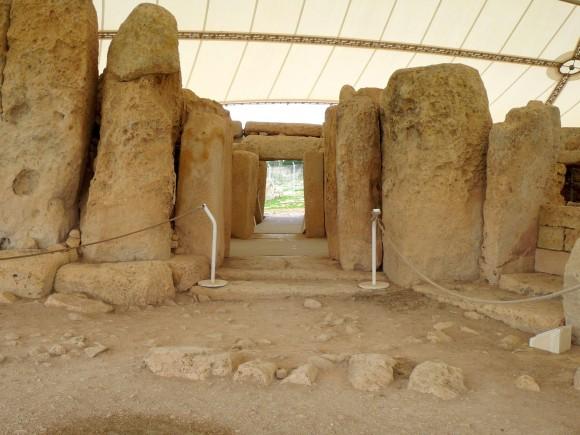

Megalithic Temples

Considered to be the oldest surviving free-standing structure in the world, the Ggantija megalithic temple site is found on Gozo, the second island in the Maltese archipelago, and dates from about 3,800 B.C.E. From artifacts so far unearthed, it appears the temple was dedicated to the Goddess of Fertility, although nothing is known about the people’s beliefs or practices.

Another great achievement, the Hal Saflieni Hypogeum on the main Island of Malta is the only known example of a subterranean structure surviving from the Bronze Age. Due to its delicate condition, access is limited to only 10 people per hour, 80 per day.

Votive figures of the Fertility Goddess were unearthed here too, along with human bones unceremoniously dumped after decomposition was complete, compounding the mystery surrounding their practices. There are pathways and chambers, and a large vaulted cathedral-like room—all carved underground.

The cathedral’s ceiling is carved in a clear-cut series of ascending circles, while paintings of spirals in red ochre decorate the walls and ceilings of the passageways leading to it. No physical evidence answers the question how the structure was illuminated or explains why such intricate architectural details such as columns and arches were fashioned underground.

I did not see all 20 megalithic temples so far discovered but I did visit Hagar Qim (pronounced “jar im”). The site is extensive and so well-preserved one could almost feel the presence of the ancients.