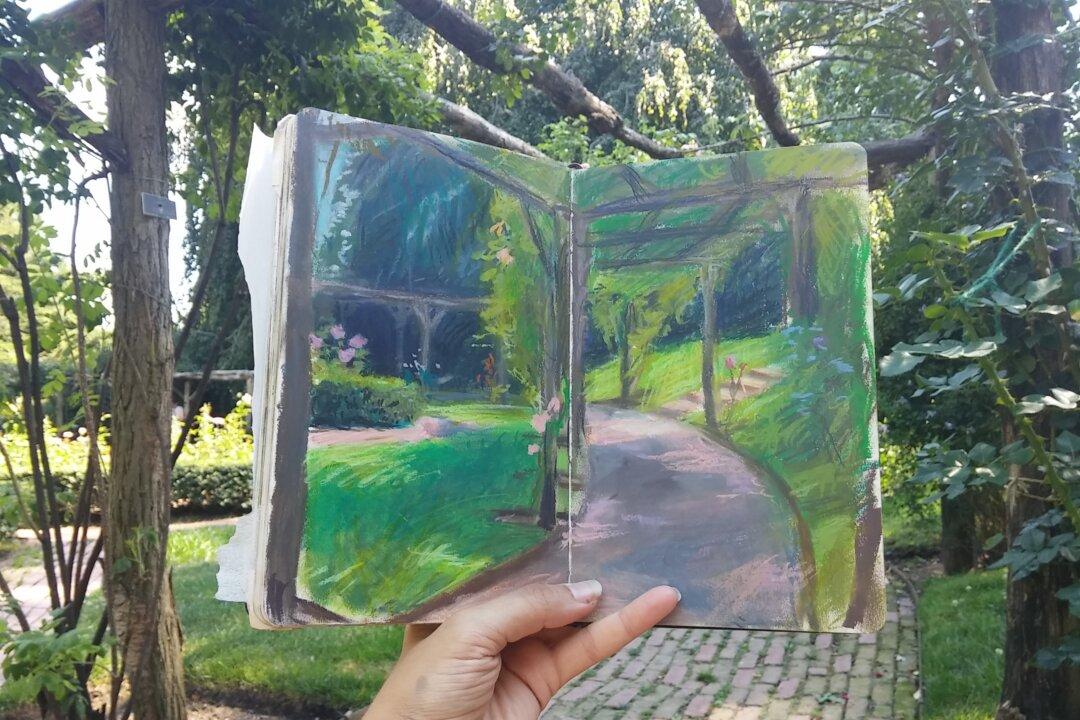

NEW YORK—Land and sea, sky and sun, fascinated the great British painter, Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851). He traveled incessantly to ports and harbors to draw those points of entry and departure—teeming with ships and people trading and going about their business. He filled numerous sketchbooks with his studies. Back in his studio he would turn those little studies into monumental oil paintings, depicting that sense of journey and freedom that he experienced at the water’s edge—often against a brilliant sun.

Turner shared his fellow countrymen’s excitement for travel, especially because 18 years of travel restrictions had finally been lifted in 1815 at the end of the Napoleonic wars. Making at least 22 trips to Europe in his life, Turner depicted every kind of port: naval strongholds, fashionable resorts, industrial harbors, anchorages in major cities, and remote river landings from different points of view.

The exhibition at The Frick Collection, “Turner’s Modern and Ancient Ports: Passages Through Time” focuses on this mid-career period of Turner’s work starting at the age of 50.