As virtuous men pass mildly away, And whisper to their souls to go, Whilst some of their sad friends do say The breath goes now, and some say, No:

So let us melt, and make no noise, No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move; ‘Twere profanation of our joys To tell the laity our love.

Moving of th' earth brings harms and fears, Men reckon what it did, and meant; But trepidation of the spheres, Though greater far, is innocent.

Dull sublunary lovers’ love (Whose soul is sense) cannot admit Absence, because it doth remove Those things which elemented it.

But we by a love so much refined, That our selves know not what it is, Inter-assured of the mind, Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss.

Our two souls therefore, which are one, Though I must go, endure not yet A breach, but an expansion, Like gold to airy thinness beat.

If they be two, they are two so As stiff twin compasses are two; Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show To move, but doth, if the other do.

And though it in the center sit, Yet when the other far doth roam, It leans and hearkens after it, And grows erect, as that comes home.

Such wilt thou be to me, who must, Like th' other foot, obliquely run; Thy firmness makes my circle just, And makes me end where I begun.

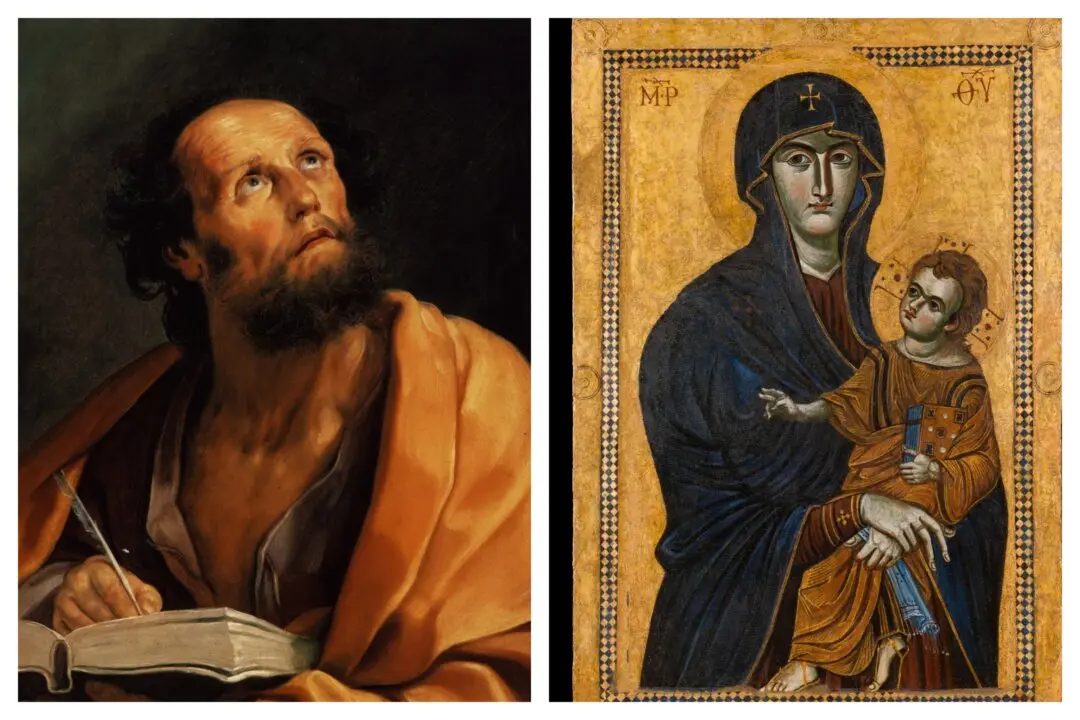

Our reason distinguishes us from the animals and grants us the ability to love rather than commit our lives to a bleak and endless expanse of pleasure-seeking. We can choose to die to self and can dedicate our lives to the service of others. However, John Donne recognized that our love is, like everything we are and do, imperfect.The highest form of human love lumbers gracelessly among the lowest ranks of angels but soars higher by far than the most steadfast of swans. Even as we make that vow to put someone else’s ultimate good before our own, we know that we are fallen. We will falter in that promise many times along the way, and will have to continually redirect our path back to genuine love above self-interest.