Among the constitutional amendments, the First is the most sacred. Its guarantees of the freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, and the right to petition have made American shores a beacon for the world. The quiet and bookish man who first proposed it spent many years reflecting on its related issues in solitude—an uncommon pastime for a politician. The First Amendment has become so fundamental to the way Americans think about themselves as social creatures that it is easy to forget the skepticism, and even outrage, that it caused in its day.

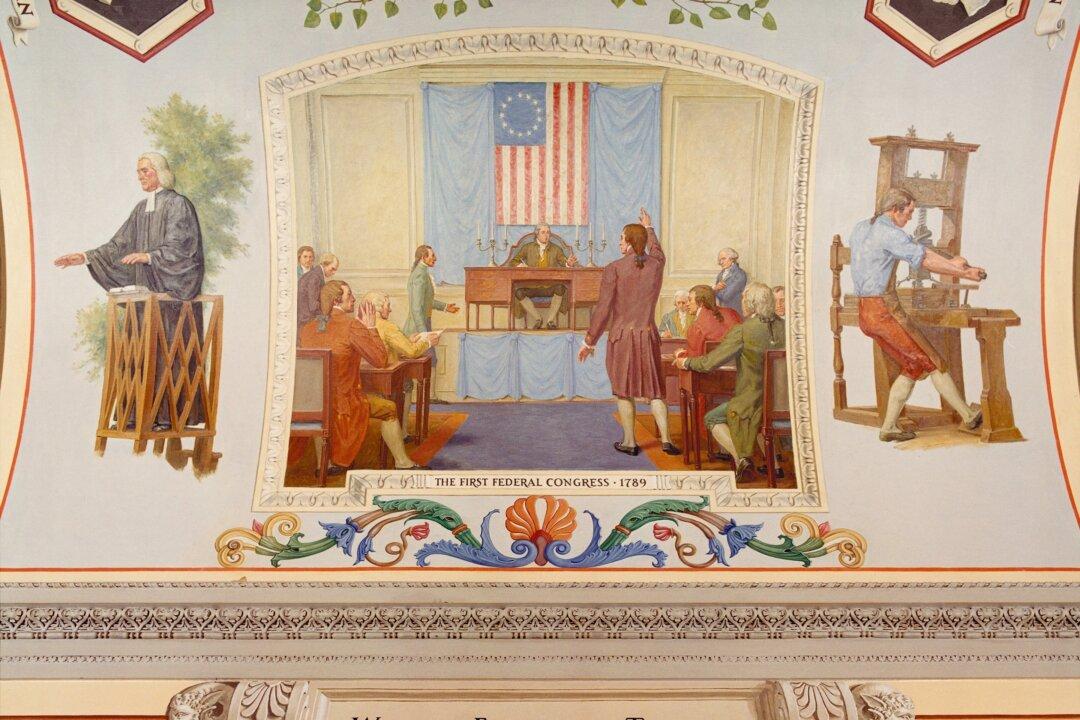

A Scholar Enters Politics

James Madison was a shrewd student of political history. Of his many thoughts on government, though, one concern was foremost. In “The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President,” Noah Feldman observes: “The subject that most animated James Madison was the freedom of religion and the question of its official establishment.” He developed an academic interest in the topic at Princeton under the Rev. John Witherspoon, who filled him with ideas of religious liberty inspired by the Scottish Enlightenment.After graduating, Madison witnessed the persecution of religious dissenters in his native Virginia, where the Anglican Church was the established religion. In a letter to a friend dated January 24, 1774, Madison described traveling to a nearby county and encountering imprisoned Baptist ministers, “5 or 6 well-meaning men” who did nothing more than publish their orthodox views. That April, he wrote: “Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind and unfits it for every noble enterprise, every expanded prospect.”