When individuals soar above their circumstances, they catch our attention. When they hold firm to timeless principles despite challenges and temptations, they inspire. When they speak the truth, do their duty, and adhere to high standards of character, they are models we should seek to emulate.

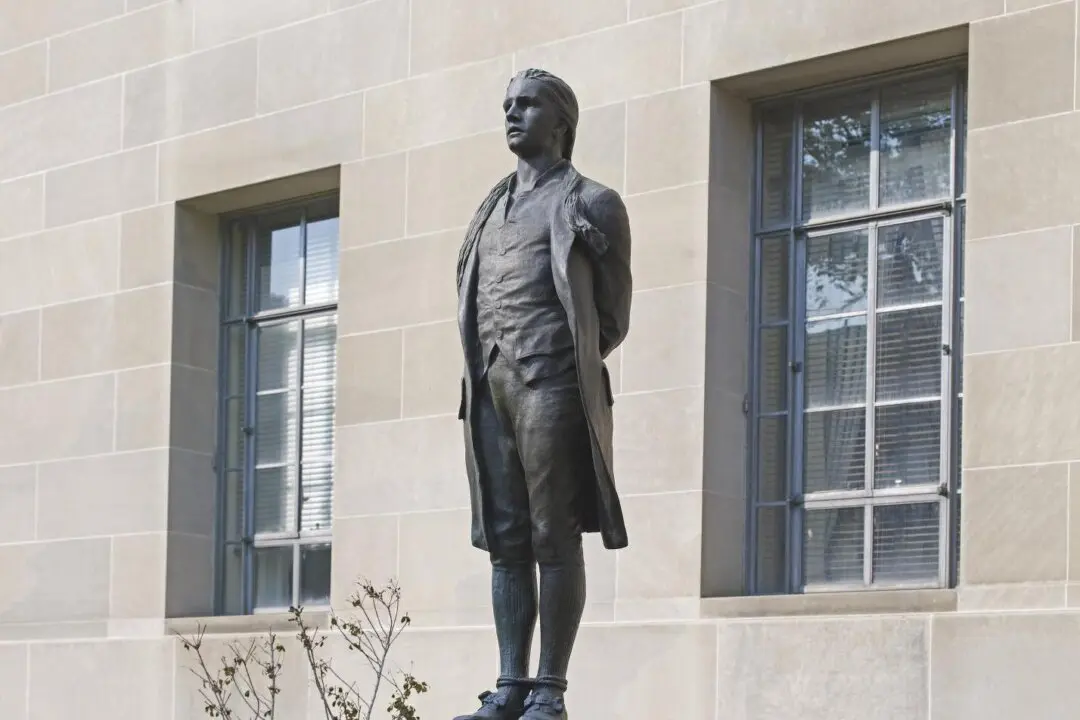

One such man was Henry Ossian Flipper (1856–1940). In so many ways, his story defies today’s conventional wisdom, just as it did in the decades he lived it.