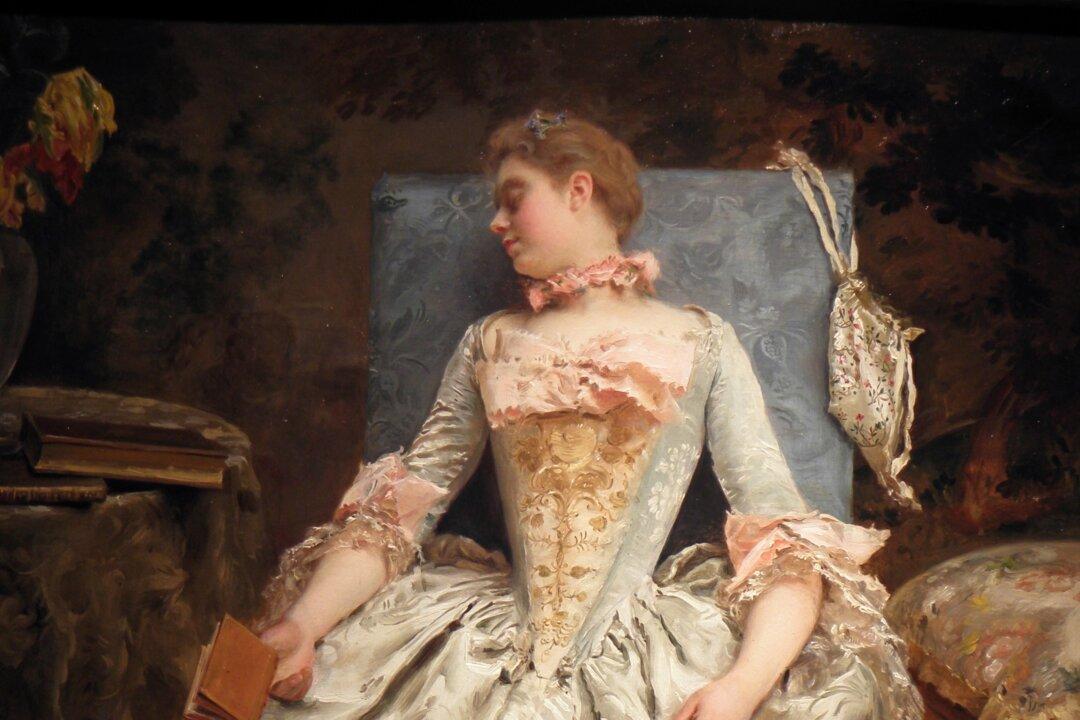

Gustave Jean Jacquet (1846 – 1909), is known among scholars as one of William Bouguereau’s top students. Although Jacquet’s subject matter was not of peasant girls or mythological scenes like Bouguereau himself or many of his other students, Jacquet quickly gained fame and notoriety for his technical virtuoso, his paintings of women, both strong and delicate, as well as historical genre scenes of women and soldiers in 16th, 17th, and 18th century costume. He painted large works on canvas with life size figures, though more often enjoyed working on smaller pieces on panel. His models were not always classically beautiful, but they were always vibrant and full of life.

Jacquet was born May 25, 1846 in Paris, France. He first exhibited in the Salon of 1865 at the age of 19, with two works, La Modestie, and La Tristesse. His career took off at the starting line and in 1867 he drew attention for his painting of Call to Arm. In the Art Journal of 1907 it mentions that it was around this same 1867 date that art critic M. Edmond said “Behold an artist, unknown today, who will be celebrated tomorrow.” It was shortly after this that his painting of Sortie de Lansquenets was purchased by the state and was put in the Chateau of Blois where it still remains.[1] He won a third class medal in 1868 at the young age of 22 with his painting Sortie d’armée au XVI siècle which was a military painting set in the 1700s. His military involvement was not relegated to painting soldiers however. He was an avid horse back rider and served in the Franco-German War (July 1870 – May 1871) as a franc-tireur of Seine. The franc-tireur of Seine was comprised of groups of volunteers who would ban together and fight independently of the organized military. He also took part in the sortie under General Ducrot during the siege of Paris on October 21st, 1870, reportedly using some of the weapons and armor he kept in his studio as props.[2] While serving, he had the terrible experience of witnessing the tragic death of the horse sculptor, Louis-Alfred-Joseph Cuvelier.