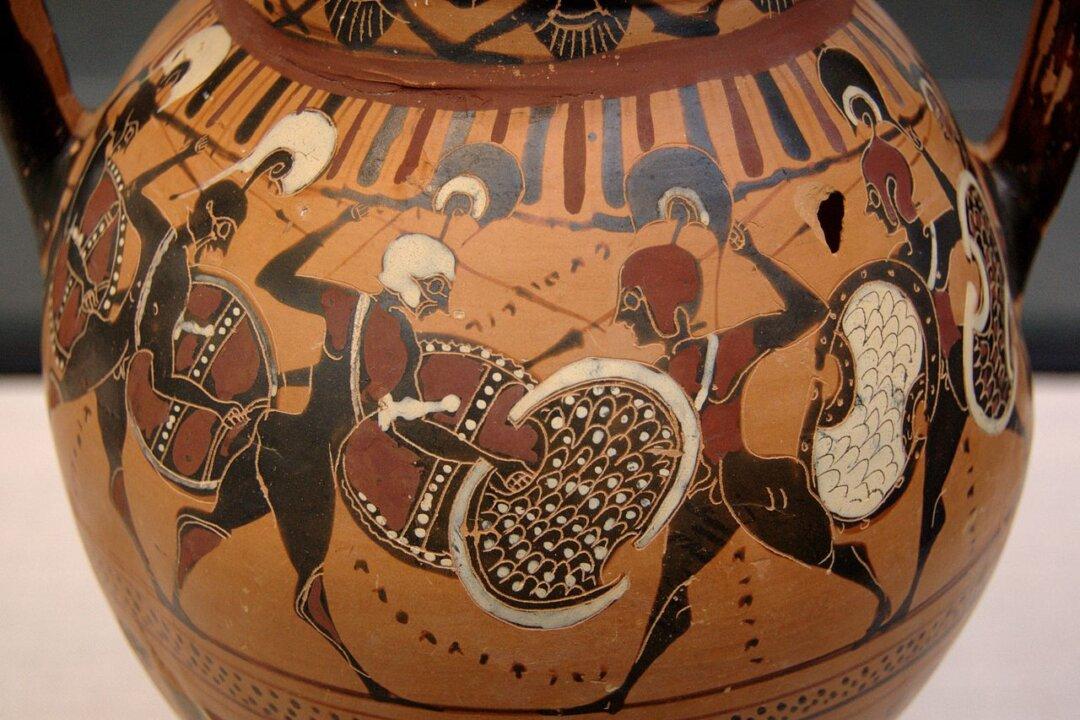

Defending one’s homeland requires the use of the most powerful weapons at hand. In ancient Greece, soldiers used the spear, sword, and shield. From about 700 to 300 B.C., the Greeks chose the aspis as the shield of choice. Hoplites, the infantry of ancient Greek city-states, defended their lands for centuries with this most important weapon.

The aspis was heavy, thick, and large, at about 3 feet long and weighing 15 to 20 pounds. Made of wood and often covered in brass, it had a bowl shape, a grip on one edge, and a leather thong in the middle to put one’s arm through. The shape, grip, and handle allowed for great mobility, given that one could hold it tight and still rest the top edge on the left shoulder, as hoplites took up the shield with their left hand so that they could wield offensive weapons with the right.