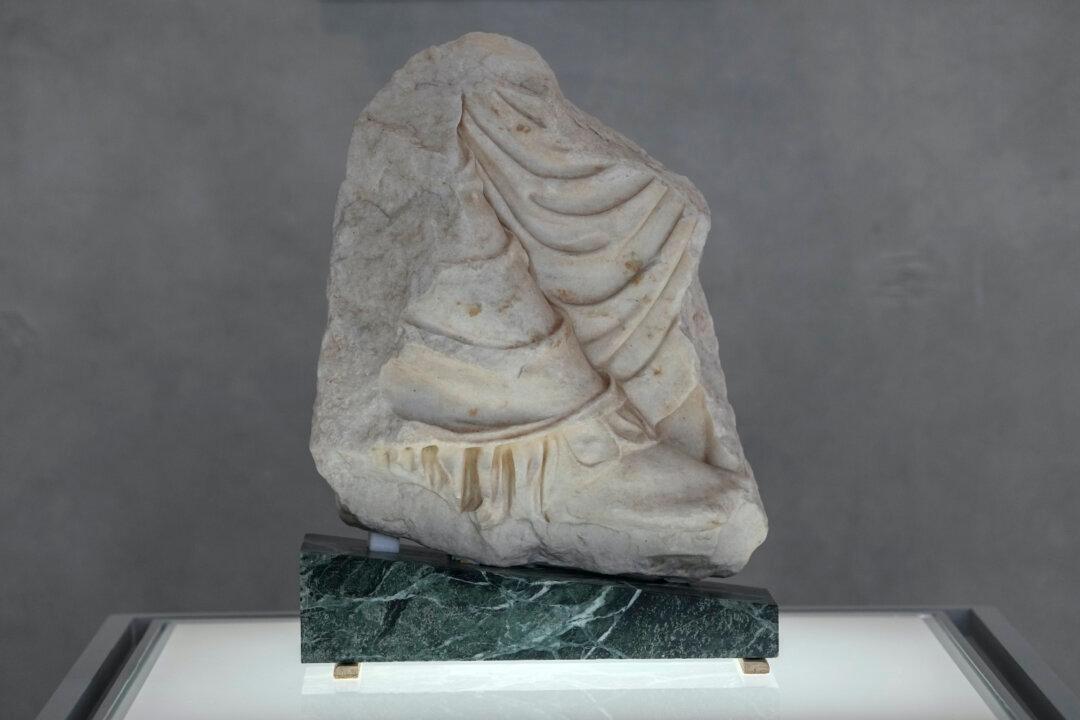

ATHENS, Greece—It’s only the size of a shoebox, carved with the broken-off foot of an ancient Greek goddess.

But Greece hopes the 2,500-year-old marble fragment, which arrived Monday on loan from an Italian museum, may help resolve one of the world’s thorniest cultural heritage disputes and lead to the reunification in Athens of all surviving Parthenon Sculptures—many of which are in The British Museum.