The Infinite

Always to me beloved was this lonely hillside And the hedgerow creeping over and always hiding The distances, the horizon’s furthest reaches. But as I sit and gaze, there is an endless Space still beyond, there is a more than mortal Silence spread out to the last depth of peace, Which in my thought I shape until my heart Scarcely can hide a fear. And as the wind Comes through the copses sighing to my ears, The infinite silence and the passing voice I must compare: remembering the seasons, Quiet in dead eternity, and the present, Living and sounding still. And into this Immensity my thought sinks ever drowning, And it is sweet to shipwreck in such a sea.

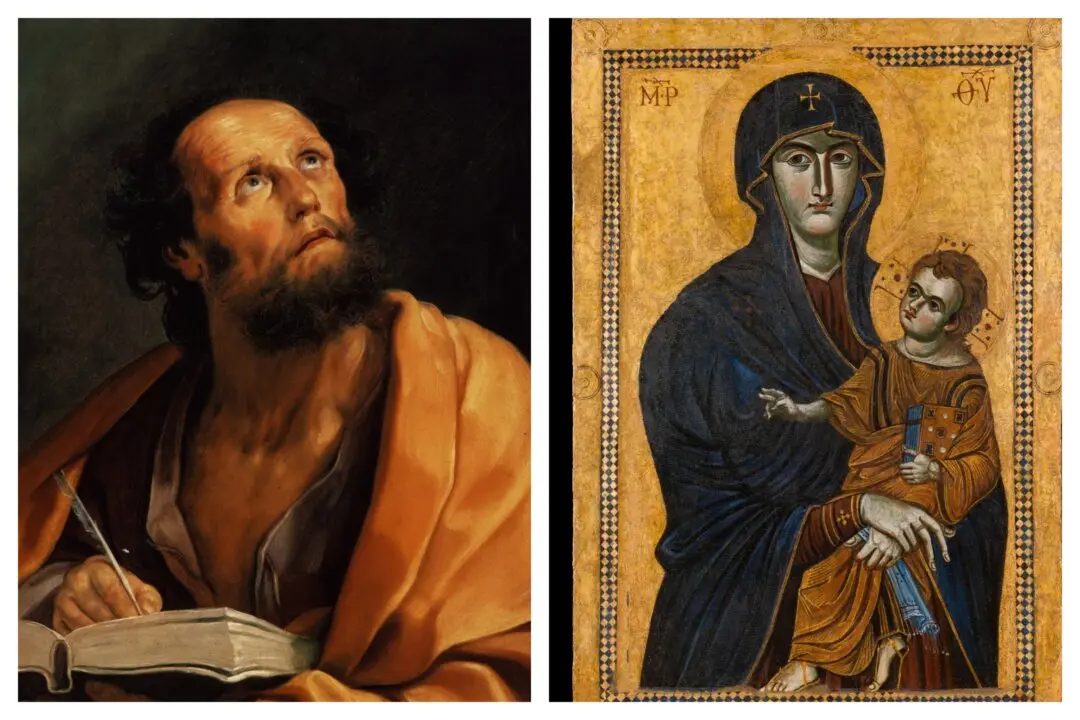

For a poem to celebrate its anniversary independent of its poet is rather rare, but Giacomo Leopardi’s (1798–1837) “The Infinite” (“L’infinito”) is just such a well-beloved poem, as we saw a few years ago with the public commemorations of its 200th anniversary. The 15 lines are so branded upon the hearts and minds of Italians that it would be a difficult feat to find an Italian who escaped their years of school without having studied it.Unfortunately, the discussion of poetry in other language involves the necessary sin of translating the untranslatable. The more beloved the poem is, the more egregious is the offense. Though the beauty of the sound is inevitably lost in every translation, I’ve chosen Henry Reed’s rendering of the poem as one of those which remains closer to the style.